Altadena Heritage asked a number of local authors and poets to tell us what Altadena means to them. The results are wonderfully varied and diverse views of our local community – from a refuge to return to after a tough day in LA, a place to watch the seasons change, a place to seek peace and nature and a place of rich diversity and sense of place.

Five of our current and recent Altadena Poet Laureates are represented as well as novelists and historians. We hope you enjoy their Odes to Altadena.

Hazel Clayton Harrison

Growing up in the Ohio Valley, Hazel Clayton Harrison dreamed of becoming a writer but she knew of no black writers. After earning her master’s degree in education, she began a career in public and private education. In the 1980s her poetry and prose began to appear in various journals and anthologies. She is the author of a children’s book, The Story of Christmas Tree Lane. Her memoir, Crossing the River Ohio, was published in 2014. Now retired from the corporate arena, she operates JAH Light Media, her own editing and publishing company, and serves as the 2018-2020 Altadena Poet Laureate for community events. She is a member of the Pasadena Rose Poets and participates in poetry readings throughout Southern California.

The Story of Christmas Tree Lane

By Hazel Clayton Harrison

Fred Nash squinted his eyes and examined the advertising copy that his secretary had left on his desk. It was June 1920. The thermometer had soared to ninety degrees outside, and perspiration soaked his shirt. But it wasn’t too soon or too hot to start planning for the biggest shopping season of the year – Christmas.

Fred was the owner of Nash Department Store in downtown Pasadena, and sales at his store had been low in the first half of the year. To increase the store’s sales, he would have to attract many new customers during the Christmas season.

“Mr. Nash, is there anything else I can do for you before I leave for the day?” Mrs. Winters, Mr. Nash’s secretary, poked her head through the door.

He glanced at her, then at his watch.

“My goodness! Is it five o’clock already? I promised Mrs. Nash I would be home early for dinner.”

He wished Mrs. Winters a good evening and slipped his arm into the sleeve of his jacket.

On the way home, ideas about ways to increase sales kept popping into his head. He took his regular route up Lake Avenue and turned left on Woodbury Road. As he drove past the neat bungalows along the road, he decided to take a detour up Santa Rosa Avenue. He loved to drive up Santa Rose because it was so scenic with its grove of stately deodars.

As he drove along the street, an idea struck him with such force, he almost ran into a storm rain. Why not light the deodars on ChristmasEve? He imagined how beautiful the cedars would look illuminated with red, yellow and green lights.

Sunset Over Hahamonga

By Hazel Clayton Harrison

On weekday evenings during the lockdown, Ollie and I took five-minute drives from our house to the Arroyo Seco Watershed. After being indoors all day, it was nice to get out of the house and get some exercise and fresh air.

If the parking lot was closed, Ollie parked his SUV on a dead end street overlooking the canyon. One of us stayed near the car, while the other walked a narrow trail that snaked along the rim of the canyon. From a marker I learned that Arroyo Seco is Spanish for “dry creek”. Locally, it refers to the stream that begins in the San Gabriel Mountains. The surrounding foothills are named Hahamonga Watershed Park after a ban of Tongva Indians who once settled there.

The foothills are not only habitats for humans, but for bobcat, gray fox, coyote, mountain lion, and deer. Mountain lions are rarely seen. But I imagined them creeping down mountain trails after dark when most people were inside. I imagined how peaceful it must have been years ago when the Tongva built their dwellings in the canyon, gathered fruits and herbs, and hunted deer and rabbit.

Khadija Anderson

Khadija Anderson returned in 2008 to her native Los Angeles after 18 years exile in Seattle. Her poetry has been published extensively in print and online. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University L.A. In 2009 Khadija was a Pushcart Prize Nominee, and her first book History of Butoh was released October 2012 by Writ Large Press. Her chapbook Cul-de-sac: an american childhood was published with Ethel in June 2020. Khadija is currently the Poet Laureate of Altadena, CA and hosts Poets & Allies for Resistance, a monthly social justice themed reading.

The Dead

By Khadija Anderson

My great-grandparents were buried in Mountain View Cemetery, May 1970

They arrived in 1909 on a ship

where the Ellis Island ledger claimed

my Besta had black hair and brown eyes

I only remember her with grey hair and glasses

In their house on Glenrose Avenue

Besta smoked small black cigars in the cool dark dining room

where the adults drank small cups of coffee

and talked for hours at a dark wood table

I don’t remember the language they spoke in their

rough 90 year old voices seeming strange

but I never understood any words they said

When I would visit, Besta-fa would hold up a small, carved

wood tiger with a wobbly head and when I smiled shyly

he would laugh in Danish

The Boulders of The San Gabriel Mountains

(after John McPhee’s Control of Nature)

By Khadija Anderson

The boulders of the San Gabriel Mountains

know when to roll

and when to stand still as stone

they have felt the lizards practicing

those masters of the

red light green light game

When the wash dries to a trickle

the boulders of the San Gabriel Mountains

shake together

send rattlesnake warnings

When the rains and mudslides come

the boulders of the San Gabriel Mountains

laugh like mockingbirds

Ode to 1963 School Air Raid Drills, Daniel Webster Elementary

By Khadija Anderson

daily jump rope daily dodge ball

hopscotch and crew cuts and flag pledge for all

all walk to school all our blonde hair

we are the country of bomb shelter prayer

run in the grass run with a ball

make a big noise like a bomb’s fall

lunch time with milk lunch in straight rows

quietly waiting for planes buzzing close

drop by the desk drop under quick

face on linoleum hands cover neck

scream while we play screaming alarm

tears stream down small cheeks we wait for the bomb

Altadena Crest Trail

(after the Station Fire 2009)

By Khadija Anderson

As we stood still near ancient oaks

a cougar came into the meadow

it watched us then disappeared

farther up the dusty trail

we found spent yucca pods

smelled sage in the late afternoon

Beyond the front range

the fire had left nothing

but grey pine skeletons

Désirée Zamorano

Désirée Zamorano is a playwright, Pushcart Prize nominee, and novelist. She is the director of the Community Literacy Center at Occidental College; she also collaborates with InsideOut Writers, a program that works with formerly incarcerated youth. She lives in Altadena, California.

Altadena

By Desiree Zamorano

I love Altadena, unabashedly. I love the light and the sky. And the foliage, and the animals, and the people—

My introduction to Altadena was through a teaching job at what was Loma Alta Elementary, now a charter school. Every morning as I drove up Lake Avenue I marveled every morning at the foothills, so close, so dramatic. I took my third graders to the Cobb Estate, to go exploring. I later marched my students to Farnsworth Park for picnics, singing silly songs there and back. I was sorrowful, later, when the state budget crisis forced the fencing off of that public park.

Those budget cuts were long ago, before I moved here. We were fortunate enough to be able to choose where we wanted to live. I wanted to live in a diverse and inclusive community. Now that I’ve been living in this town for over twenty years I have an appreciation for its seasons and its rhythms. How quiet it is as night is emphasized by the occasional roaring presence of an unmuffled motorcycle, distant fireworks, the plaintive cry of an owlet, or the distant shrieks of communicating coyotes. I love the silence our nights bring.

In autumn the sun slants bright, through still green leaves, casting shadows on the streets pavement, yards, and homes. The air at last hints of coolness, the din of freeway traffic far and faint. When the temperature dips below 70 degrees, I think, “maybe now is time to unpack my sweaters!” Somehow, it never stays cold enough long enough for my tastes.

As we move into our Californian winter the deciduous trees drop their leaves, but we remain surrounded and shrouded by elms and deodars. Deodars! Those magnificent imports who raise their limbs and display their holiday colors and celebrations on Christmas Tree Lane.

What wonderful opportunity to walk up and down a car-less street, a chilly night, listening to the local school bands after the speeches of the local leaders.

Winter is the perfect time to hike the Sam Merrill trail, to catch a glimpse of the shimmering ocean in the distance. To breath, to feel free and unfettered. To return home and light a fire.

With spring comes spectacular colors, of foliage and peacocks and hummingbirds. I cherish the hummingbird nests on our alcove. Spring is when two young bears clambered from my backyard, into the front, and disappeared down the street. Maybe to take a dip in a nearby pool.

Summer is a challenge here, as the desert reclaims its due. Which is why the outdoor summer concerts are a particular delight, gathering us, hot and sweaty to dance, to sing, to sparkle and shout.

Altadena year round is filled with doves and crows, parrots and scrub jays, woodpeckers and carpenter bees. These all accompany a morning coffee, or late afternoon cocktails in the garden.

We are in the sweet spot between the rural and the urban. We are home.

Teresa Mei Chuc

Teresa Mei Chuc was born in Saigon, Vietnam. She is a fellow of and teacher consultant for the Los Angeles Writing Project and teaches writing and literature at a public high school. She is founder and editor in chief of Shabda Press and a member of the Coast to Coast Poetry Press Collective.

Millard Canyon

By Teresa Mei Chuc

canyon of bay laurels

tákape kakáaka

ancestral lands of the Tongva people

before this area of running

water, ancient stones and waterfall

was called Millard Canyon

where the newts swim in streams

and the frogs are camouflaged on rocks

and the blackberries glisten

where the waterfall sings and the children laugh and play in the pool

the wind speaks to me, caresses my hair

my bare feet touches this earth and water as I stand beneath the falls watching the fern grow along the cliff

the water clear and cold, the stones smooth beneath my toes

I listen to the stories that the falling water tells me

and the acorns from great canyon oaks are scattered along the ground

here, black bears, coyotes, deer, bobcats and mountain lions have lived for time immemorial

mockingbirds sing, their voices bounce off the canyon walls

a family of quails scurry by through the bushes of Tovaangar

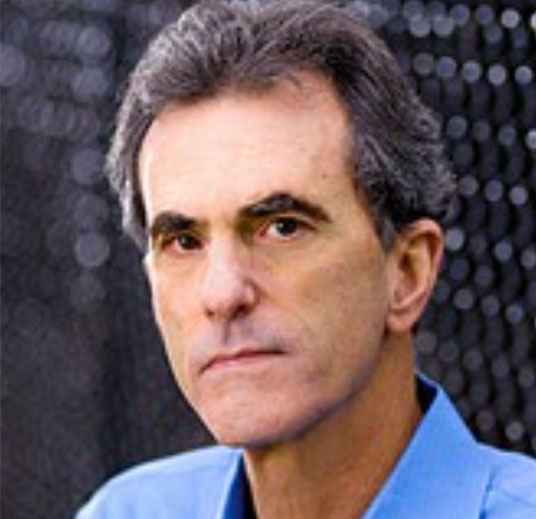

Jervey Tervalon

Jervey Tervalon is the author of All the Trouble You Need, Understand This, and the Los Angeles Times bestseller Dead Above Ground. An award-winning poet, screenwriter, and dramatist, Jervey was born in New Orleans, raised in Los Angeles, and now lives in Altadena, California, with his wife and two daughters.

Altadena Love

By Jervey Tervalon

I moved to Altadena 23 years ago and it’s been a great 23 years. I’ve lived other places; I was born in New Orleans and was lucky enough to be raised in the Jefferson park area of Los Angeles. Jefferson Park at that time was largely African American with many families with a connection to the south; Texas, or Louisiana and quite a few folks from New Orleans. I graduated from Dorsey High School, near Baldwin Hills and then attended UC Santa Barbara. It all kind of makes sense. I moved from a culturally complex ethnic Gumbo like New Orleans, to a little New Orleans in the Jefferson Park area I was raised in, and then left for what I thought would be the white world of UCSB. It was certainly white but soon I began to see them not as white people so much, but as people I lived in the dorms with, ate in the commons with and studied with. Then my black girlfriend dumped me for a white guy, and I was on my own. I discover through my Latina girlfriend, Latino culture and then though my Jamaican friend another compelling and complex culture. Later I married a black woman whose family help integrate Montecito. We moved to Pasadena to a cute house on Lincoln that we didn’t know was next to a freeway. Then we moved up hill to Altadena to the new gated development, La Vina. Then we divorced and I moved down the hill to the only house in all of Altadena/Pasadena with a yard that I could afford. My daughters loved it, and we loved living in Altadena outside of a gated community.

Altadena is truly a community and a diverse one. I don’t want to live in a community without black neighbors or Latino/a neighbors or queer neighbors. I want to see Asian folk in the neighborhood so that I don’t have to worry so much about racist lunatics when my Chinese wife, Jinghuan runs many miles in the early morning though she runs with Myra, and Pedro and Andy, a rainbow of people who represent the best of our community. There’s great affluence in Altadena, but I don’t have more than a passing interest in stately manors. I’m interested in life and connection and belonging to something that affirms all of us. In New Orleans people often greet each other with the phrase “What you know good?” and that’s the excuse to talk to someone you don’t know to learn about them and share what you’re about. That’s what I feel about Altadena, I belong here as I’ve belonged nowhere else and I will forever be grateful to call it home.

Michele Zack

Michele Zack has lived in Altadena with her husband Mark Goldschmidt since 1986 — with the exception of 8 years in Thailand.

Since returning in 1998, she authored and received national recognition for popular histories on Altadena and Sierra Madre, and worked with the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West in writing and programming grants to improve the teaching of American History at K-12th grade levels.

She and Mark are both past Altadena Heritage board members and chairs, and Michele currently represents AH on the LA County committee charged with preserving Owen Brown’s gravesite in the hills above Altadena.

Altadena Story

By Michele Zack

My Altadena story starts far away, in Bangkok, Thailand — where husband Mark, baby Natalie, and I, moved in 1990. Mark and I were not kids. (I was almost 40, Mark is 5 years older). We wanted “one last adventure” before settling into that scary thing we daren’t speak out loud: middle age.

The adventure lasted eight years… Eight. Very. Long. Years. More like a lifetime. I was a journalist and wrote speeches for Prime Ministers – who change with alarming frequency in Thailand. Mark designed resorts, working in places like Bali, Lombok, Ankor Wat in Cambodia, Laos, and the Seychelles. Natalie and I sometimes tagged along.

Life was exciting, offering us professional opportunities we never would get back home. We considered becoming permanent expats, travelling the world, raising our daughter as a citizen of that world.

Our feelings oscillated between exuberance — and home sickness. Full of difficulties, challenges, and charming, interesting people, Bangkok is brutal. You can afford household help there, and excellent international schools and medical care. Food’s great, too. On the downside, getting the lead levels of your child’s blood tested regularly because of pollution, anxiety of being illegal aliens for four years before we got our residency papers, navigating a huge ugly city with traffic you wouldn’t believe — was exhausting.

We often had fun, living in a foreign culture with strange politics, new friends, and frequent coup d’états, but, did I mention it was exhausting? Navigating our daily local world of Bangkok was the hardest part. There were so many things we could do nothing about. Or even comment on — it wasn’t our country. Problems we thought should be solvable, like getting street dogs fixed and vaccinated, cleaning up the filthy canal on which our daughter rode a boat to school every day, or doing something about traffic.

Years passed. Homesickness and elderly parents won out over exuberance. We’d always told ourselves: “If we ever move back to Altadena, we will become better citizens. Because we can.”

And so we did. We moved back to our 1920s house on Marengo Avenue in 1998, and dug into our local world. Spending two years researching and thinking about, and then writing Altadena’s history, is one of my life’s great good fortunes. Mark was soon roped in to being on the board of Altadena Heritage, then on the verge of going bust for lack of volunteers.

Guess what? Getting stuff done here is also very difficult. But unlike in Bangkok — for us, anyway — it often turns out to be possible. It takes work and time, and frustration is often involved. With vision, volunteering, and mostly perseverance — Altadena Heritage has made a huge difference in the life of our town the 20 years since we returned here. There’s real satisfaction in improving the place you live, like fixing up your house. A headache, but when it’s done you are really glad you made the effort. Then you have fun and party with neighbors.

Heritage either led the charge, or was a big contributor to, projects like our Community Standards District, Hillside Ordinance, Old Marengo Park, Woodbury Median and parkway tree planting, Farmers Market, Triangle Park, Altadena’s “Welcome and Thanks for Visiting” signs, and most recently — preserving Owen Brown’s gravesite. Our organization designated 7 Altadena Heritage Areas (AHAS!) including Janes Village and The Equestrian Block. And we regularly hold events, such as workshops on trees, lawn removal, saving energy, making jam, and so on — plus great parties and home tours. Before Covid, these brought us together in person regularly… and they will again.

Altadena Heritage has been the great vehicle, the big civics lesson of my life. What I longed for back in Bangkok, Thailand — being part of positive change — I found here. Don’t like something? Have a better idea? Be prepared to work locally, even if being a citizen of the world is still your first choice.

Miles Corwin

Miles Corwin, a former Los Angeles Times reporter, is the author of six books. The Killing Season was a national bestseller. And Still We Rise was awarded the PEN USA West award for nonfiction. Homicide Special was a Los Angeles Times bestseller. His novel Kind of Blue was named one of of the Top Ten First Crime Novels by Booklist. His two other novels are Midnight Alley and L.A. Nocturne. He graduated from UC Santa Barbara and received his M.A. at the University of Missouri School of Journalism.

Altadena

By Miles Corwin

When I was covering crime for the Los Angeles Times in the 1990s, the city was beset by a murder epidemic. The epicenter was South Los Angeles, where there were more than 400 murders a year. I was so overwhelmed with the sheer volume of homicide, that I took a leave of absence from my job and wrote a book about a quiet genocide taking place south of the Santa Monica Freeway. I spent a summer trailing homicide detectives to crime scenes, watching them tell families a loved one died, attending autopsies, sitting in on suspect interviews.

My only respite from the ever-present anguish was at the end of the day, or often early the next morning – after spending all night with detectives – when I would exit the Pasadena freeway, cut over to Hill, and head up to Altadena. My days were spent in impoverished neighborhoods where the murders mounted and many of the streets were without a single tree or patch of grass, so devoid of vegetation and color they looked like black-and-white photographic negatives.

When I finally reached Altadena, however, my mood immediately was lifted by the multicolored landscapes I passed: the lavender Jacaranda blossoms, purple Mexican sage, magenta bougainvillea, and the pastel array of roses that graced so many front lawns.

Sometimes, as I traversed the side streets, I’d get out of my car and stretch – my back usually ached from standing on the sidewalk at homicide scenes for many hours – and I’d see the San Gabriel Mountains bathed in brilliant sunlight. Often the scent of orange blossoms or jasmine would waft by.

I was often so distraught after talking with the heartbroken families of murder victims that I wasn’t ready to return home because I needed to decompress. At these times, I’d stop at the Altadena library, wander into the garden in front, relax on a bench for an hour or two, surrounded by lush landscaping, and appreciate the Zen quietude of the little hideaway. Sometimes I’d check out a book. Often, I’d doze. When I’d wake, I’d return home, go over my notes, and was ready for another day of trauma and tragedy.

In the years since then, whenever I was away from home researching stories or books, wherever I traveled, however stressful, I was revivified when I spotted the San Gabriel Mountains in the distance, because I knew I would soon be home in Altadena, which has always been a restorative refuge for me.

Naomi Hirahara

Naomi Hirahara is an Edgar Award-winning author of multiple traditional mystery series and noir short stories. Her Mas Arai mysteries, which have been published in Japanese, Korean and French, feature an Altadena gardener and Hiroshima survivor who solves crimes. Scheduled for publication in August 2021, her next novel, Clark and Division, follows a Japanese American family’s move to Chicago in 1944 after being released from a California wartime detention center. She, her husband and favorite Jack Russell Terrier live in Pasadena. For more information, go to her website, www.naomihirahara.com.

The Altadena Public Library building, designed by architect Boyd Georgi, was opened in 1967 when I was five years old, the prime time for a child to start reading. Books quickly became my time-traveling portal, transporting me from the hot strawberry fields of Florida to the historic Lower Tenement neighborhood of Manhattan to Holland where a small fishing village attached wheels to a schoolhouse and homes to entice the return of storks.

I came to the library seeking more stories and windows to the world. My appetite was insatiable. The library, with its open architecture and garden, was a placed where I felt like I belonged.

Note: Books referenced are Lois Lenski’s STRAWBERRY GIRL; Sydney Taylor’s ALL-OF-A-KIND FAMILY series; and Meindert DeJong’s THE WHEEL ON THE SCHOOL.

Fun fact: Naomi and the estate of Sydney Taylor share the same literary agent.

Jessica Abughattas

Jessica Abughattas is a poet of Palestinian heritage, born and raised in California. An alumna of Pepperdine University, Abughattas has been awarded a Kundiman fellowship and an M.F.A. in poetry from Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work has been published in Lit Hub, Redivider, Waxwing, and elsewhere.

She has recently moved to a house she loves in Altadena and is currently the co-Poet Laureate of Altadena.

Animal Feeling

By Jessica Abughattas

I wanted to wake with you and the cat

in a small house at the foot of the mountain

where birds sing wildly into the dusk

and coyotes scavenge from yard to yard

stalking timid dogs and fat neighborhood cats,

but not ours. Ours tiptoes in at the first ray

and climbs over us – a gymnast, sweet boy.

You must be there now. The cottage

between Hen’s Tooth Plaza and the hiking trail

that leads to an abandoned train station.

They must stay doing that even without me.

Of course they do: the birds proclaiming nothing,

the cats yawning from their roofs

and drainpipes, the lawns humming

wet with dew, the plaza sitting vacant

awaiting the keys of laborers, the rattlesnakes

hissing on the trail, early sun just hitting

their skin, the tracks collecting dust

And staring out into the city below,

where I have gone. I wake alone

in a room on the boulevard: cars

are rushing to offices, tires screeching

as they go, and people waiting on the sidewalks

for a ride or their dog to piss.

It all keeps going on without you.

The little flame in the sky, it just has to

go and touch us all.

Colleen Dunn Bates

Colleen Dunn Bates is the publisher of Prospect Park Books, a longtime writer, and a resident of and business owner in Altadena.

Inevitable Altadena

By Colleen Dunn Bates

Although not as egregiously as “unique,” the word “inevitable” is all too often misused. Think about it: Only one step in any process can actually be inevitable. If, for example, you say it was inevitable that you’d end up becoming a lawyer, because everyone in your family is lawyers, lots of things would have to go a certain way for you to become a lawyer—like getting into law school, for starters. So objectively, it was not inevitable that I would end up an Altadenan, not by a longshot; my life plan at 21 called for settling in Santa Monica. Yet in retrospect, every step along the way makes it seem like Altadena was the only possible outcome.

I grew up in the ‘60s and ‘70s in Los Angeles, and when I was a teenager, I thought Pasadena was where fun went to die. As for Altadena, I didn’t even know it existed. Cut to 1992, when my husband and I had a toddler and were worrying about the then-limited school options in our Silver Lake neighborhood, plus the fact that we lacked a child-friendly yard. Friends with young children had just bought a house in Pasadena, so I did the once-unthinkable and started looking east. Right away, I fell in love with Altadena: its architectural diversity and richness, its trees, its quiet, its quirkiness. But the extra 15 minutes’ drive up the hill would have added a half-hour a day to our already-stressful commutes, so we found a beautiful, freeway-adjacent west Pasadena home and burrowed in for 28 years.

But Altadena kept calling. First came the hikes that I’d take with my dog and my friends: Chaney Trail, Sam Merrill, Altadena Crest. Next was the lure of the Altadena Town & Country Club, which we joined in 2001 so we could play tennis and our kids could swim. When I’d drop the kids for swim-team, my dog and I would fill the hour by walking the oak- and pine-dappled streets above the club, and I’d pick a new favorite house on every walk. The next step in the path toward inevitability came in 2012, when my older daughter graduated from college and found a little rental house to share with her girlfriend in Altadena.

They worried that it would be too provincial for 20 somethings, but they fell in love with it.

Two years later, I had the opportunity to buy a small piece of commercial real estate, but my budget was too modest for Pasadena. So I focused on, of course, Altadena, and found a neglected three-unit building on Lincoln, renovated it, and turned into the home of Prospect Park Books and the studios of two talented photographers. Bit by bit, Altadena was sinking its hooks in.

This year, in an unexpected frenzy of activity, our two daughters and daughter-in-law bought a two-on-a-lot fixer-upper in Altadena, moving in just before the pandemic hit. And with my husband’s retirement (no more commute!) and the pandemic-enforced change in lifestyle, we started keeping an eye out for the perfect empty-nester house, closer to ATCC, our daughters, and our soon-to-arrive grandson… talk about sinking the hooks in! I found the dream house on the corner of Meadowbrook and Sinaloa, and it all happened so fast that it hasn’t quite sunk in.

And yet, it has been sinking in for nearly three decades—the inevitability of Altadena, our unintended and yet totally predictable forever home.

Michelle Huneven

Michelle Huneven was born and raised in Altadena, California. She received an MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop, spent many years as a food writer and restaurant critic, then published four novels Round Rock (Knopf 1997), Jamesland (Knopf 2003), Blame, (Sarah Crichton Books, FSG, 2009), and Off Course, (Sarah Crichton Books, FSG, 2014). Her fifth novel, Search, is forthcoming, probably in 2022.

She also teaches literature and creative writing at UCLA.

She lives in Altadena with her husband, environmental lawyer Jim Potter, along with a rescue dog, a black cat, a talkative African Gray parrot, and 6 chickens.

Ode to Altadena

By Michelle Huneven

I was born in Altadena 67 years ago. Altadena air was the first air I breathed, her trees, sky, streets, and mountains, the first I ever knew. Our modest, integrated neighborhood was the world to me. Altadena imprinted me, body and soul, with the way things should be.

I came into consciousness in a little one-bedroom house on El Nido Drive, way over by the Arroyo Seco. My father, who had moved to Altadena with his family in 1923, had bought a quarter acre of subdivided lemon grove in 1934, when he was 19. Fourteen years later, itching to settle down, he began building a tiny house on the property. Shortly, he met my mother at a socialist meeting on Highview, in one of the Gregory Ain’s Park Planned homes. Nine months later, they married. I was the second daughter, born in 1953.

We soon outgrew the tiny house–the bedroom I shared with my sister was an enclosed front porch–so my father built a larger home on the same lot, one inspired by Ain’s modernism, with high wood beams, clerestories and a white stone roof. I went to Franklin Elementary when it was a brand new school; then to Eliot Junior High, and graduated at 15 from John Muir High, class of ’69.

Despite early vows to live all over the world, and be as unlike my parents as possible, I did not, in fact, fall far from the tree.

Thirty-two years after I left for college, I moved back to Altadena on September 10th, 2001, the day before the world changed. Amid the ensuing national tumult, it was a glad return to the known. Here again was the hoo-hooing of mourning doves, the cat piss menthol of eucalyptus, the same prickly oak leaves. Here were the familiar ridgelines of Mt. Wilson and Mount Lowe; the same ambles up the Arroyo Seco past JPL into the canyon’s coolness. Past and present mingled and settled into a deep sense of home.

A former resident of my property, the Princeton sociologist David Popenoe, claims our block is one of the most socio-economically diverse blocks in the country.

There are mansions to the north, modest Janes cottages to the south, and some hodgepodge infill randomly stuffed in between—of which my small 1953 stucco cube on its large, flag lo tis a prime example. I live next door to Michele Zack, a friend I made on the first day of high school, more than half a century ago. Other neighbors introduced me to the man I would marry, Jim Potter, who happily joined me here.

I love the diversity of Altadena, the presiding mountains, the raffish, idiosyncratic yards and gardens and architecture. The supermarkets of my youth—the Shopping Bag, the Market Basket, and the Pantry may be gone, but we have our very own Super King and its glorious profusions (sometimes, there, I think the whole world has come to Altadena). Yes, sidewalks would make neighborhood strolls easier, but I like that we haven’t worn away all our rustic edges—or installed a single parking meter. Roosters crow; horses and their riders wait their turn at the McDonald’s drive through window. For all the changes, Altadena still feels much as it did 65 years ago, with its mature trees, backyard stables, excellent hardware store. We have more than our fair share of artists, writers, and NASA scientists; eccentrics, soreheads, and Nobel prize winners.

I breathe Altadena’s air, drink Rubio Canyon’s water, eat fruits and vegetables we grow in Altadena soil. My DNA? No surprise. Altadena, purebred.

Elline Lipkin

Elline Lipkin is a poet, academic, and nonfiction writer. Her first book, The Errant Thread, was chosen by Eavan Boland for the Kore Press First Book Award. Her second book, Girls’ Studies, was published by Seal Press and explores contemporary girlhood in America. Her poems have been published in various contemporary journals and she has been a resident at Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Dorland Mountain Arts Colony. She teaches poetry for Writing Workshops Los Angeles and is also a Research Scholar with UCLA’s Center for the Study of Women. From 2016-2018, she served as Poet Laureate of Altadena and co-edited the Altadena Poetry Review.

For Lucille B. Jones

Matriarch of Marigold Street, Altadena, CA

By Elline Lipkin

The first time I saw you

you told me how your husband

had brought you, “a young bride

from North Carolina,”to be nearer the Pacific and the mountains,

their wall of shadow and compressed heat

cast against the house he built,

roots grown deep over 60 years.

Now, he’s a ghost you talk to in odd hours,

the lilt of your accent calling him back.

Making your way down

the drive for the daily paper,

you were always gladdened to see me

and my newborn, also at the end of our drive,

head cradled in my palm

as we also bent awkwardly to lift up the news,

his fuzz of hair edging the carrier,

uncertain feet dangling out.

A compass of neighbors checks if your paper

is still there past 10, the mail past 4,

peeks through your east window for movement,

watches the light settle at night on the west.

We know you’re safe again when the Webster’s

pharmacy half-truck delivers its rounds.

“Old age is not for sissies,” you said often,

late in your 90s, resolute, housebound,

everyone subtly watching you,

as you once surveyed passersby,

peering out from your porch.

New family, old guard.

The lemon trees shadow us both,

their dappled waft of blossom and decay

drifting across our yards like an unseen canopy,

the reach of invisible arms sheltering us all.