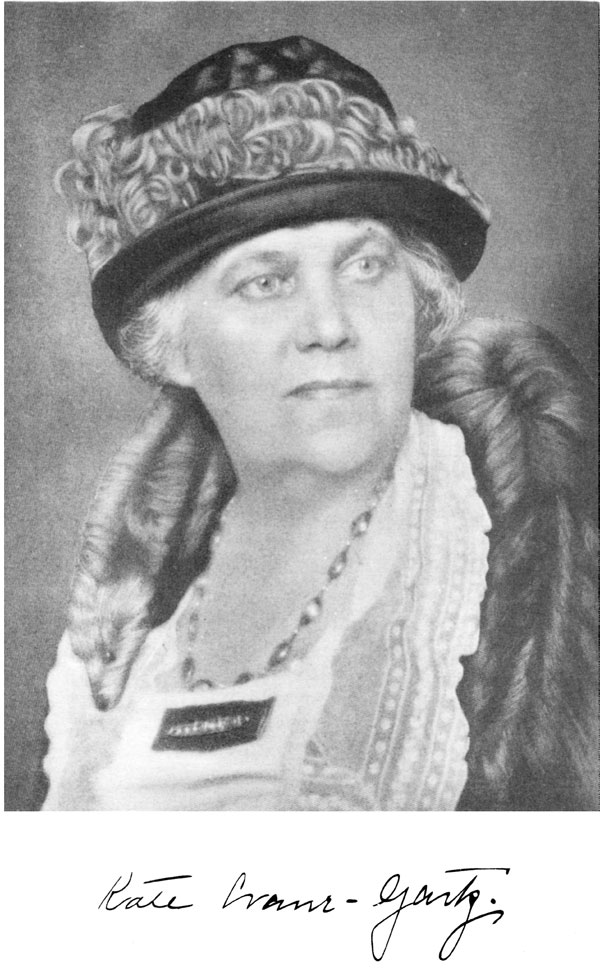

Kate Crane Gartz – 1865-1949 – Altadena’s Parlor Provocateur Was More Than That

By Michele Zack

Among the most notable of many prominent Chicagoans settling in Altadena after the turn of the century were Kate Crane Gartz and her husband Adolf, who arrived in 1908 with two sons and a daughter. Kate, born in 1865, was the heiress of the Crane Plumbing Company; the couple built a $25,000 showplace, “The Cloister,” on the northwest corner of Mariposa and Santa Rosa Street. They soon extended the planting of deodars up Santa Rosa from Mariposa to Altadena Drive.

Adolf applied himself to useful, conventional, kinds of civic engagement such leading the Improvement Association, adding pavement and lights to Altadena streets (which he characterized as “dark as the Egyptian night”), and chairing the Rubio Cañon Land and Water Company Board for 20 years until his death in 1930.

Kate was less orthodox: she aimed at nothing less than changing the world for the better — from Altadena. She came by her Progressive Era fervor honestly: in Chicago her father Richard was a major philanthropist and founding supporter of Hull House, among the first settlement houses in America that provided child care, employment, education, legal advice, and arts and culture to new immigrants. He also supported Upton Sinclair as the muckraker worked on The Jungle, his famous expose of Chicago’s meatpacking industry, which led directly to the establishment of the Food and Drug Administration to protect America’s food supply.

Kate’s brand of social and government reform was further activated by tragedy: two of her young daughters perished in the infamous Iroquois Theatre Fire in 1903 in Chicago — in which escape routes were locked, 602 died, and another 250 survived terrible burns. Public safety reforms, along with women’s and workers’ rights, found in her a life-long champion.

Kate established a salon under the rose arbor at The Cloister, which became the center for intellectual, cultural, and civic activities in Altadena from the teens, and continued long after Adolf’s death.

The Cloisters occupied the north-west corner of Mariposa and Santa Anita Avenue.

Photos: Altadena Historical Society

Regular salonistas included Upton Sinclair and his publisher wife Mary, Charlie Chaplin, Albert Einstein, Aline Barnsdall, King Gillette, and a raft of leftie publishers and intellectuals. They batted about socialist-minded solutions to society’s problems, and supported numerous Progressive projects and candidates for 30 years. Kate bailed Sinclair out of jail several times, most famously after his arrest for reading the Constitution to unionizing San Pedro dockworkers in 1923; she was also a key supporter in his failed bid for governor in 1934.

Well into old age, she penned letters of advice to Franklin Delano Roosevelt widely published in newspapers; these were anthologized in booklets and published by Mary Sinclair. Kate lived in the Cloister until her death in 1949, and is entombed in Mountain View Mausoleum with Adolf.

Deprecatingly, detractors dubbed her a Parlor Pinko, or Parlor Provocateur, for the progressive and outspoken positions she took that belied her class and privilege. This moniker, however, ignores a life of real work and accomplishment, far from parlor, in an activist career that spanned more than five decades.