Hunting the Highlands

By Michele Zack

Careening on a jubilant bender through Los Angeles’s muddy streets at Christmas, 1873, Southern-minded Dr. John Griffin chortled that he’d finally got the best of those “Damn Yankees!” Anyone in earshot, including journalist Benjamin Truman (who wrote it down) learned that he’d sold 4,000 dry acres up the Arroyo to a naive group of Iowans — land where “a respectable jack rabbit wouldn’t be seen.” Shockingly, these fools paid him $6.60 an acre for it!

The price was brought that low (from the point of view of Pasadena’s founders) by Griffin’s partner Don Benito Wilson, who threw in 1,400 extra acres at the last minute to seal the deal. This included the future Altadena in the outwash beneath the mountains.

The claim about jack rabbits was pure hyperbole. It is well-documented that the land teemed with wildlife— particularly jack rabbits! Many seasonal rivulets and canyon water sources in the late 19th century supported food supplies for deer, puma, bears, gophers and other small mammals, and birds such as quail. Fish were prevalent in canyon streams. Boys and young men coming to the new settlements arrived with, or soon developed, hunting skills — walking miles and spending days to track and bring home mostly rabbits for the family pot.

Game for the family pot

Alice Eaton Smith remembers brothers Will and Ben Eaton “loved to go hunting for jack rabbits in the hills and they brought back the cottontails, too.” Alice was familiar with this abundance; her family had lived by the mountains at Fair Oaks Ranch next to what is today called Eaton Canyon, since the end of the Civil War. Her father, Pasadena founder (not from Iowa) Benjamin Eaton understood the land’s potential, brokered the deal with Griffin, and invested in it. When Alice was four years old the family moved south to be closer to schools, neighbors, and other marks of civilization appearing with the rush of educated Midwesterners to Pasadena. But her big brothers still headed to the hills to hunt.Before the move, Eaton always had concerns at Fair Oaks

dealing with wildlife. He was determined to stop the elusive bear plundering his bee hives, and in 1879, awake one night with a “howling toothache”, set out with his old Sharps musket 50-70 single shot to hunt the culprit. He was startled to discover it was a Grizzly! By this time, Ursus arctos horribilis was uncommon here. After a first shot, with a very quickly loaded second he stopped him at a distance of 10 paces as the wounded animal charged. It took four men the next day to load the giant into a cart, and he was taken down to town. “In a few moments it seemed as if the whole population of Pasadena was gathered at Williams’s store to see the bear… school was dismissed so the children would have a chance to see it. The animal measured 7 feet 10 inches, but weighed only about 500 pounds, for he was very poor…” Eaton recollected in Hiram Reid’s 1895 History of Pasadena. More quotidian, Eaton reported killing 11 rattlesnakes his first year at Fair Oaks (1865), “three of them having 11 rattles each —” as well as various predators (brown bears, mountain lions, and wildcats) who found good eating in his livestock and garden.

Levi and Luna Giddings and their son Eugene came here in 1874 with a large clan, and soon founded Mountain View Cemetery. They shared many pioneer hunting stories, as did the hunt-loving Britain William Allen, and the Woodburys. Giddings “always kept hounds” on his ranch (near the mouth of Millard Canyon), usually five or six, to keep down the chicken-stealing fox population. Levi related an incident in which his hound Cash treed four “big wildcats” in a single tree. Giddings shot two, Cash attacked a third that jumped down from the tree, and a fourth sprang on the struggling duo. One cat escaped, and miraculously Cash survived, “though he was laid up for some time with the bites and scratches the cats gave him.” Cash was with him one of Giddings first years here when “I got 37 deer within two miles of the house”

The Elite Set and “Sport” Hunting

It is difficult to grasp how quickly Pasadena and the coming of more genteel, often sick, Temperance-minded immigrants began changing both eco-systems and social landscapes. Most were less rough and ready than “family pot” hunters, who were hardly rustic bumpkins. In the 19th Century, being a jack of all trades was a survival skill: Eaton was a Harvard-trained lawyer and water engineer, Giddings an abolitionist whose uncle was in Congress, John Woodbury a banker and aesthete, and William Allen of the Sphinx Ranch had been a cotton broker in Egypt for 23 years. But many of the more religious among the new settlers frowned on growing wine grapes, the Highlands’ (as Altadena was then known) chief crop— and most were city-bred folk who preferred to distinguish themselves by forming literary and arts societies, and in scientific, business, and social pursuits.

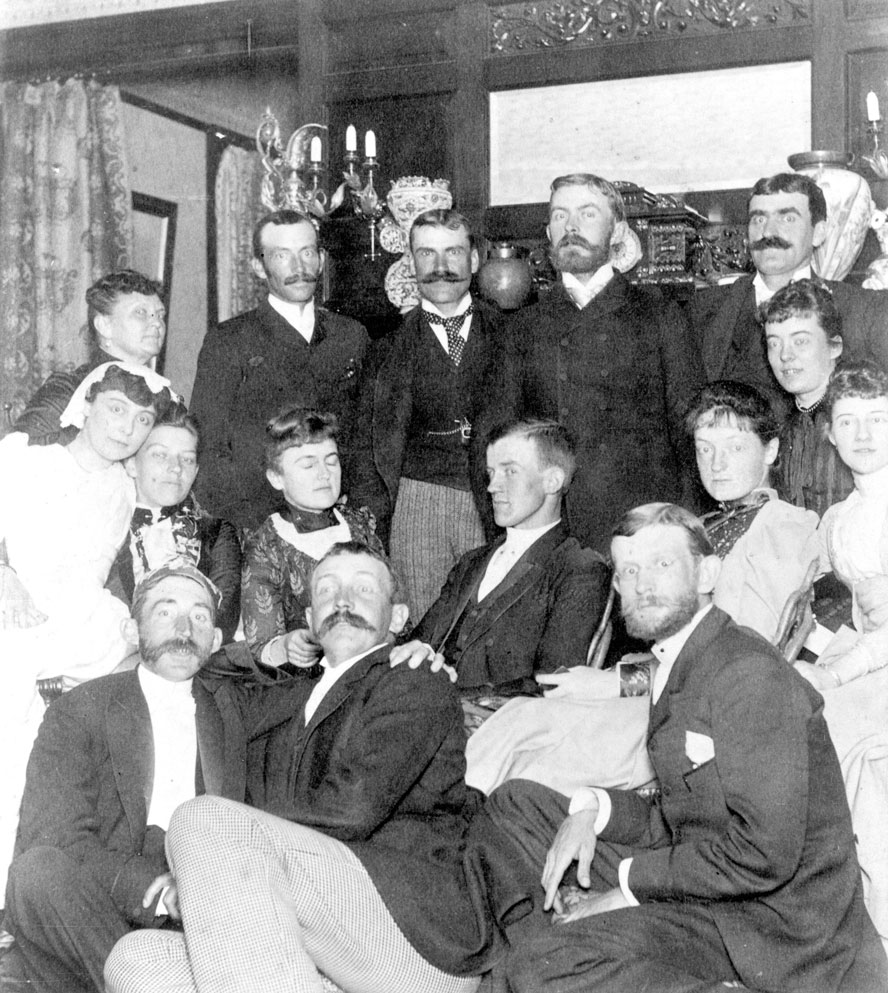

Among this contingent was Bayard T. Smith, known as the “Chesterfield of Pasadena” for his natty dress and impeccable manners. A publisher, Pasadena postmaster, political influencer, and real estate developer, he moved up from his Pasadena Oak Knoll Ranch to Altadena the year our community was founded, 1887, to a Fredrick Roehrig designed mansion he commissioned. On the northeast corner of Mariposa and Santa Rosa, it was the site of many highbrow social events, and also the first informal meeting of the Valley Hunt Club.

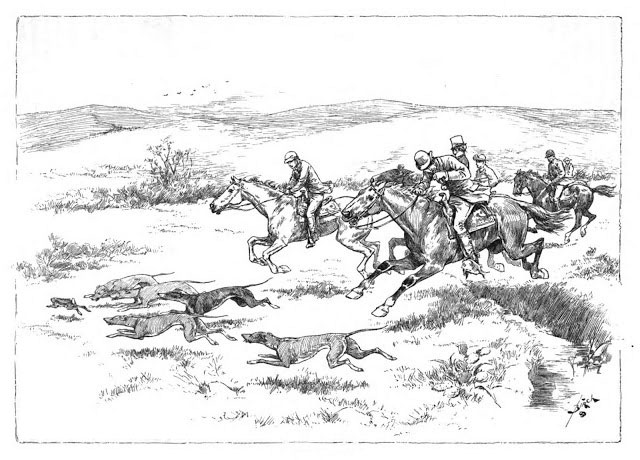

This club marked the social ascendance of “sport” over “family pot” hunting, though the latter variety continued until real estate and agricultural development gradually squeezed out game. Members of the Valley Hunt Club held hunts and elevated social occasions, and introduced gentler alternatives to earlier rabbit rousts where one’s seat on a horse (or even having a horse) was less appreciated than ebullience and colorful storytelling. Among the new civic entertainments cooked up by the Valley Hunt Club was a “Tournament of Roses” featuring a Rose Parade, and an organization (for years limited to 100 members) offering social advancement and female influence. A popular but short lived “Gladiator Race” where toga-dressed contestants in chariots galloped around a ring in the Arroyo revived the earlier spirit, but was discontinued as too wild and dangerous to co-exist with the floral parade. Within a few years, the blood-sport crowd had football games to satisfy that particular lust.

The story is that a group of Bayard’s pals were hunting the wilds of Altadena soon after his grand residence was built. A fierce storm broke out, Smith wasn’t at home, so they broke in. While enjoying this shelter and warmth, they decided to form a British-style hunt club to promote “the hunting of jack rabbit, fox, and other wild game with horse and hound.” The group (significantly, women made up half the original members) included McNallys, Greenes, Banberrys, Bandinis, Staats, Carters, and others from prominent families. It formally organized in Pasadena in1888.

Hunting the wilds of Altadena decreased as people settled here and homes, vineyards, roads, railways, piped water, and other development impacted wildlife habitat. In the early 20th century, new animals were introduced, including possums and squirrels, for hunting and eating, but never took off. While killing certain animals is still allowed (either by permit to hunt, or by other means if the critter is categorized as invasive or a “nuisance”), shrinking open space and shifts toward nature preservation have all but ended the practice. Co-existing with wildlife, appreciating what we have left, and sharing our environment are today’s cultural norms. Shopping at grocery stores replaced more time consuming, strenuous forms of hunting and gathering. People unhappy with nuisance wildlife today tend to use traps for control, which is reasonable, and poison, which is not — because it goes on to sicken and kill birds and other animals eating poisoned carcasses.

Those who hunt in the 21st Century mostly travel far, even out of state, or to the Pacific Ocean to do it. One backyard vintner in Altadena did for a time hunt invasive fox squirrels ravaging his grapes, tossing his prey into the freezer until enough accumulated for a casserole. But for every one downed, another popped up to claim the decedent’s territory — so he gave up. There were a few bow-and-arrow, or cross-bow hunters going after deer in our foothills. The most famous was a fellow styling himself Ram-bow — but he and others were pursued and chased off by locals with smart phones and safety concerns.