Altadena’s Beginning as Mecca for the Ill

By Michele Zack

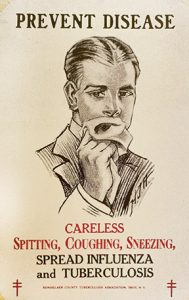

Ours is not the first pandemic in which hearts have been gripped by fear of contagion and death, when coughs and sneezes caused panic, and when people fled cities for clean country air.

In the United States, the end of the Civil War and completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was such a time, when tuberculosis provided extra or the primary motivation to migrate west. TB had become the main cause of urban adult death by around mid-century.

Altadena’s settlement and early years were utterly intertwined with this massive westward movement and health crisis. Unlike the single year of pandemic we’ve lived through, this earlier epidemic persisted from 1865 through the early 1900s.

At the end of the immigrant trail, the newish state of California was coincidentally undergoing a defining experience and forming its identity. Less known and understood, but arguably as significant as our Gold Rush (1849-59), was our Health Rush. An accepted estimate is that 25% of the hundreds of thousands of westering people moved for reasons of health. Not every ill person made it to California, but of those who did, most ended up in the state’s warm, dry south. Many reinvented themselves here, and became Californians.

At the end of the immigrant trail, the newish state of California was coincidentally undergoing a defining experience and forming its identity. Less known and understood, but arguably as significant as our Gold Rush (1849-59), was our Health Rush. An accepted estimate is that 25% of the hundreds of thousands of westering people moved for reasons of health. Not every ill person made it to California, but of those who did, most ended up in the state’s warm, dry south. Many reinvented themselves here, and became Californians.

The study of climate, called climatology, evolved from the mid-19th century in tandem with tuberculosis in crowded, industrializing cities in the East and Midwest. Although the tuberculosis bacteria was identified in 1860, no reliable cure was discovered until WWII. Many therapies were tried. Hundreds of thousands died, and fear of the disease pulsed through society. From the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Centuries, moving to a healthy climate with plenty of fresh air was the most-recommended therapy, and not just for TB — but for all pulmonary diseases, as well as other conditions including alcoholism, neurasthenia, and more generally, health broken by the Civil War. After 1900, isolation became understood to be the best way to stop the spread of tuberculosis, and the sanitaria movement began containing the disease.

But for a full generation before, the most popular cure placed Altadena in its cross hairs. According to climatology precepts, the ideal situation for human health was a dry Mediterranean climate one to two thousand feet above sea level. Altadena: check! Early land advertisements lauded the perfection of our location “above the noxious fogs of Pasadena,” adding that it was also not too high.

Neither “miasma” (thought to be carried by fog) nor thin, freezing, night air to impede healing in the Highlands, as our area was known before 1887. Iowan John Woodbury borrowed the name Altadena that year from a defunct nursery for his new subdivision.

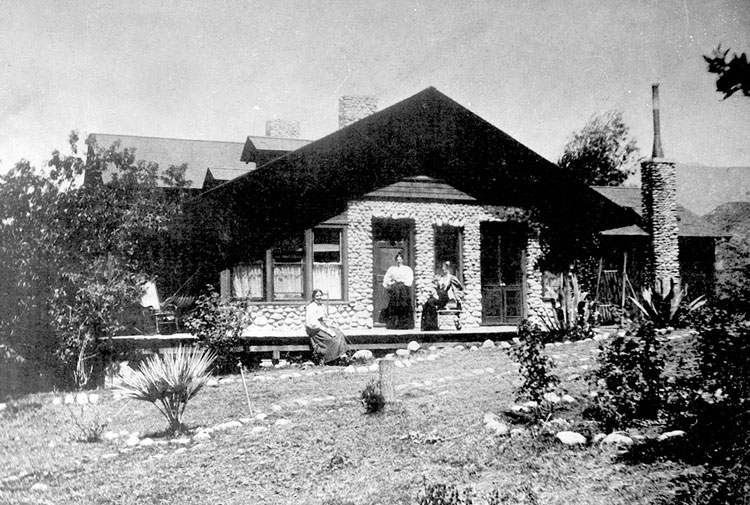

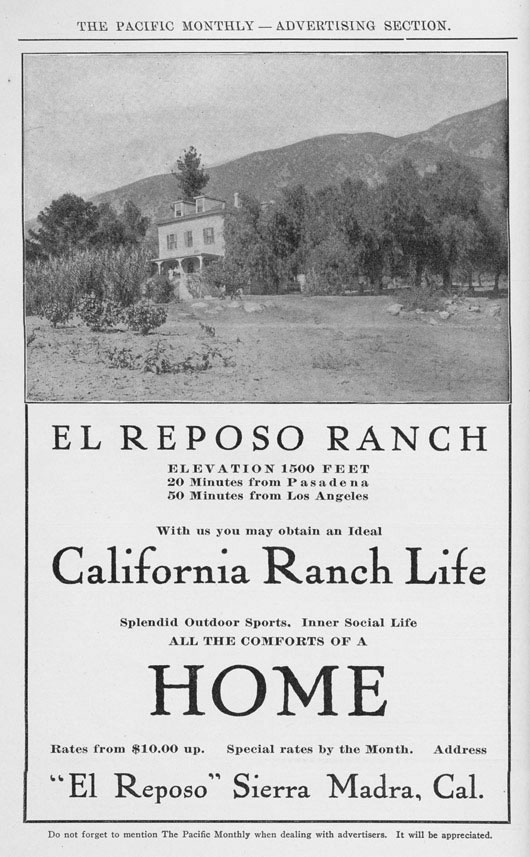

It is no surprise that health seekers of some means, education, and imagination landed here and in other settlements along the San Gabriel foothills from the 1880s through the 1920s. Altadena’s specific attractions were many: rail lines up from Pasadena (one of Southern California’s earliest, toniest settlements founded by cultured, tea-totaling, Midwesterners); the adjacent world-renowned health resort of Sierra Madre Villa; and neighboring Sierra Madre, the target of a sophisticated sales campaign aimed at the “well-off ill” of New and Old England. It didn’t hurt that Altadena’s land was a bit cheaper and more sparsely populated than its neighbors, while similarly situated against the gorgeous San Gabriel range.

While the health-seeker story has been often described, its legacy as a major force in California culture hasn’t yet been fully appreciated. Our state is still associated with redemptive qualities — and the idea that its citizens are health-obsessed has only increased with time. In the 19th century this message was spread by real estate developers and gallons of ink in newspapers, books, publications, and personal letters. Altadena offers a fascinating example supporting the importance of health-seeking to regional identity, as well as to our community’s very existence.

At least seven institutions dedicated to treating respiratory illness and avoiding ill health in vulnerable children were established here between 1887 and the mid-1920s — despite a population of only a few hundred at the beginning and a few thousand by the end of the period. Several survived through the 1930s and a few, beyond. And more informal health camps and resorts, as well as what today would be called board and care homes, became rooted in Altadena and the foothills behind. La Viña Sanatorium, the most famous and long-lived, was a non-profit institution established by Dr. Stehman in 1911 to treat less well-heeled sufferers in the Progressive Era.

The fact that Altadena never incorporated as a city was key to health and land use here. Unlike Pasadena, we lacked the power of the ordinance to restrict health-related or other businesses. In the city to the south, a cough was enough to get one evicted from a boarding house; that is why Mountain View Cemetery, established to serve Pasadena, had to locate outside its limits. Levi Giddings, who arrived in the Highlands in 1875 and bought a few thousand acres, turned over some of his land very profitably to found the cemetery in 1881. Today it, along with the Mausoleum added in the 1920s, is Altadena’s longest continually operating business (and still owned by the same family.) Giddings, along with even earlier arrivals including Benjamin Eaton (1865), developed water resources as soon as they came, making the arid wasteland directly north of Pasadena saleable. (see Altadena Heritage Newsletter, Fall/Winter 2020 pages 8-9.

The founder of Sierra Madre, N.C. Carter, purchased 845 acres at $20 per acre in 1881 from Lucky Baldwin, the same year brothers Fred and John Woodbury bought 937 acres of the future Altadena for $5 an acre from Pasadena. The two communities make interesting “comps.” Their geography and water resources were similar, but they were marketed differently. Carter, from America’s first planned industrial town of Lowell, Massachusetts, had recovered from TB in California, and was a born salesman who had found success dealing real estate for Lucky Baldwin. His brilliant sales campaign included an “amateur newspaper” mailed to prospective buyers in the Northeast, and aimed straight at the well-off sick. He personally escorted private train car loads of “lungers” (as TB sufferers were informally called) to Sierra Madre from New England every year, and targeted the same group in England, where he made deals with pulmonary specialists to refer certain patients to him for the “Sierra Madre Cure.” He sold land in smaller plots at $40-$60 per acre.

Typical Altadena buyers, by comparison, were farmers and vintners (and a few millionaires) who paid less for larger tracts purchased from various sellers rather than a single slick developer. Growth this decade was more off-hand, but attracted a continuing trickle of investors. Southern California values began catching fire as the 1880s unfolded into a boom that peaked — but turned to bust, just as the Woodburys launched Altadena. Timing, as Lucky Baldwin often stated, was the key to success in real estate.

Major depression took up most of the 1890s, with a single bright exception in our area being the Mount Lowe Railway, opened in 1893. Altadena remained a backwater that thousands of rich tourists and health seekers saw from train windows on their way to Mount Lowe’s fancy resorts. The most well-known of these who gave Altadena a second look was Zane Grey, who passed through as a dentist on his honeymoon in 1906, and moved here permanently in 1920 after becoming rich as an author who defined the west for the rest of the county.

When Sierra Madre incorporated in 1907, its first official acts were establishing a public health department and declaring a central zone covering most of the town that banned institutions “for the care and treatment of mental, contagious, or pulmonary diseases.” Tent-houses, where less affluent health-seekers lived, were also prohibited, as city officials struggled to “dispel the illusion… that this city is nothing but a big consumptive camp.” Successive ordinances passed by younger, healthier newcomers (with no nostalgia for the town’s tubercular founders), restricted small board and care homes to two patients; hotels, restaurants, camps, and resorts posted signs barring entry to those with pulmonary disease; and newspaper editorials suggested that Sierra Madre’s needy ill be taken care of at “Dr. Stehman’s Sanitarium four miles to the west” — otherwise known as La Viña Sanitarium, in Altadena!

An absent/far flung county government, sparse population, and ideal location worked to make our community a mecca for the ill — especially as they were pushed out elsewhere. Sick people didn’t appear to cause problems here, at least not ones that left records — perhaps because there were so few records! A.C Vroman, who moved to Pasadena for his health, did mention in his memoir a camp of indigent sufferers in a tent camp in the 1890s behind Altadena.

Many people recovered out west, and it is important to note that most never saw the inside of a formal institution because they were cared for by female family members at home. Health problems were driven deep underground in the 19th Century; the prevalent belief being these were best kept within the family; personal archives suggest almost every family was touched by this scourge. Those selling real estate certainly didn’t stress numbers of ill people accumulating above and below ground in the west, and public death records didn’t become standard until after 1900. To approximate the size of the “Health Rush” historians rely on obituaries, church and parish records, personal letters, memoirs, and on decoding advertisements: institutions and western “Ranches” catering to the sick often didn’t mention this in print. Some scholars reckon that once the Transcontinental Railway made moving west a possibility for the health-compromised, half of its riders fit that description.

The 25% health-seeking share of western immigration could be conservative, and reflects all modes of transportation including covered wagon and sea travel. It is impossible to state an absolute number, because records don’t exist. Scratch below the surface of Southern California in this period, however, and every indication is that the impact of illness was far larger than public presentation suggests — a clear example of history whose importance has been partially “erased.”

Altadena and other unincorporated foothill communities differed from Pasadena and Sierra Madre because cities, not LA County, enacted restrictive health ordinances in this era. These new instruments of civic control most often targeted businesses before county zoning kicked in. Commercial activity here consisted of farms, vineyards, a graveyard, stable, transportation, and institutions such as Dr. Gleason’s “Las Casitas Sanitarium” — and no entity appeared to regulate or record anything beyond land sales.

Adele Gleason was a female physician/entrepreneur who purchased land in foothills overlooking El Prieto Canyon in 1887, from Owen Brown, son of John Brown who led the raid on Harpers Ferry. Its remote location might have led to its failure, although in 1894 another doctor, O.S. Barnum, leased it. Today, it is a residence on Gravelia Street in The Meadows neighborhood; Owen himself was buried close by after contracting a fatal chest cold walking home in the rain from a Pasadena temperance meeting in 1889.

Many other institutions came and went. Chaney Sanitarium perched above Millard Canyon north of Loma Alta; New York homoeopathist founder Edwin Chaney established a 14-cabin retreat around 1900 that did well, until rains eroded his hillside property and the nearby, much larger La Viña, opened as a non-profit institution in 1909. Esperanza (Hope) was built by Dr. Frederick Melton, an Austrian army veteran, east of Hill Avenue and north of Mendocino Street in 1902. He lived nearby on Holliston Avenue, and grew grapes, peaches, and Eucalyptus. Esperanza changed hands, but Dr. Melton remained in Altadena until his suicide in 1934, following the deaths of his wife and son.

Several businesses here catered to the ill, but perhaps the most forward-looking and successful of Altadena’s institutions was Hygeia Hotel, named for the Greek goddess of health. It had its own stop on the Pacific Electric Railway (successor to the Mount Lowe Railway) taking passengers from Los Angeles to Altadena Junction at Lake and Calaveras, and on to Rubio Pavilion, Mt Lowe, and beyond. Established the same year as La Viña, Hygeia’s founder Dr. W.J. Geirman took a muscular approach to restoring health. And because he didn’t accept TB patients — but those suffering from asthma, alcoholism, nervous disorders, and generally in need of being “built up” — he enjoyed exceptional success. Sunshine, fresh air, vigorous daily exercise, cold baths, and showers (to boost the adrenal system) were his regime’s bedrocks. Clients ate a diet of vegetables, fruits, nuts, and unlucky deer caught foraging hotel gardens — who enriched a popular venison stew. He planted the 28-acre bench of land east of the top of Lake Avenue with hundreds of trees, creating an idyllic setting of tents, cottages, and a two-story lodge that drew health seekers through WWII. Before Mount Lowe resort burned and permanently closed in 1936, it was one stop or a short hike from Hygeia to Rubio Pavilion, a popular dance hall, restaurant, and post office, with miles of trails and wooden stairways hung with Japanese lanterns clinging to fern-decked canyon walls. (There was more water in the canyon in those days.) No wonder many of Dr. Geirman’s patients reported restored health after a stay in Altadena!

The Progressive Era, a period of intense social activism and political reform, was in full swing from the turn of the century — and landed squarely in Altadena. Public health policies were a top concern, with reformers delving deeper than before to tackle root causes of social ills. The Preventorium, built south of Mariposa on the bank of the Arroyo in 1922, aimed to provide a healthy 24-hour-a-day environment for boys whose home lives were deemed to make them vulnerable to disease. Like Five Acres, (established by Los Angeles County in South Pasadena, and moved to Altadena in 1926), but privately funded, it focused on boys who were orphans or half-orphans with mothers unable to support them. And the Preventorium (later called the Pasadena Health School for Boys) and Five Acres, as well as La Viña, were all designed by famed architect Myron Hunt. In this era, beautiful architecture and environment were understood to have significant effects on human development — especially on children deprived of such advantages by circumstances of birth. Landscape architects Florence Yoch and Lucille Council designed Preventorium’s grounds, retaining mature trees and creating an orchard and a garden where boys grew their own vegetables. They also raised goats, chickens, and rabbits, and attended school surrounded by long, low buildings with Spanish-tiled roofs. The Preventorium — today, The Sycamores — precipitated Altadena’s first recorded public fight (unsuccessful) to stop a group home or institution from coming here. Today’s residents are familiar with this tradition.

California’s “health rush” was fading by the 1920s, as illness as a driver of immigration slowed dramatically, sanatoria began proliferating around the country, and infection rates dropped. The terrible Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19, tragically taking the lives of young people very quickly, eclipsed slower-moving TB as public health fear #1. The epoch blended into the Progressive Era, Arts and Crafts Movement, and the Roaring 20s. Our health rush, however forgotten or overlooked, planted long-lived seeds: health food/concern with diet, various natural therapies, sleeping porches and other “close to nature” activities like camping, and life style elements still associated with our state. Health-seekers lived in, died in, or passed through our community. Many reinvented themselves as healthy people, and even many who died contributed to ideas and a cultural identity that survive today.

Extra summers on earth was the gift Altadena gave to many, and it seems fitting that we take a moment to appreciate all who sought redemption here, having lived through a pandemic that has taken the lives of more than 580,000 Americans and 73 Altadenans in just over a year.