Photos by Eric Reed/SVCITY

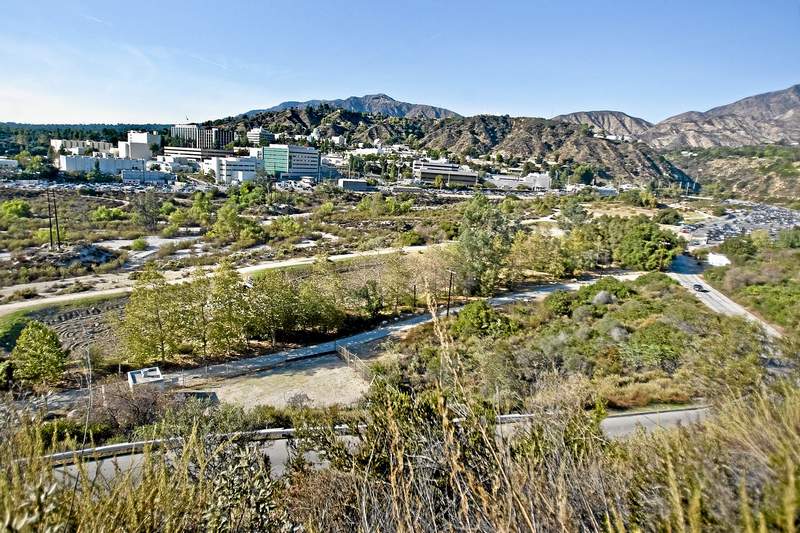

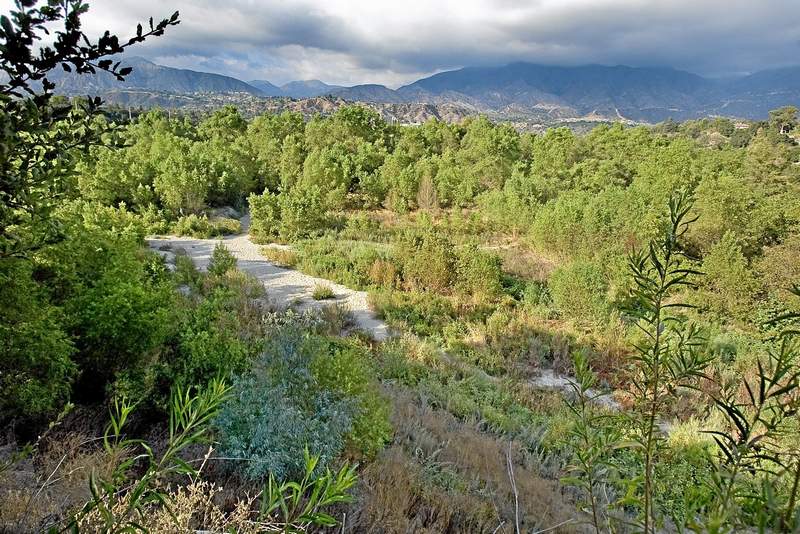

The great pioneers of Pasadena described the Hahamongna watershed and the Arroyo Seco as a place where trout swam in crisp waters, webs of flowery vines and oaks blotted out the sky and hunters scored bears and foxes for display in their Los Angeles homes.

However, the connection between downtown L.A. and nearby, natural playlands has been severed by 100 years of county dam projects, concrete channelization of waterways and arsonist-fed wildfires.

To add insult to injury, such fragile ecosystems encircling today’s Pasadena, Altadena, La Canada Flintridge and central Los Angeles are threatened by a county sediment-removal project that is outdated, unbalanced and a violation of environmental laws.

At least, that’s the view presented by Tim Brick, executive director of the Arroyo Seco Foundation, during a forum sponsored by Altadena Heritage attended by 115 people at the Altadena Community Center on Thursday night.

Brick, along with Dave Douglass, a geology professor at Pasadena City College, and Josephine Axt, chief of the planning division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineering and lead author of a multi-year study on the Arroyo Seco Watershed, spoke and answered questions about the history of these wild areas and the proposed clean-out of Devil’s Gate Dam and 71 acres of Hahamongna Watershed Park that will require 400 truck trips a day from April to October over five years.

The county Board of Supervisors approved a plan in November that would remove 2.4 million cubic yards of sediment. Engineers say this is the proper amount in order to keep the dam functional and prevent flooding in a major storm. A special working group convened by the Pasadena City Council recommended that taking 1.1 million cubic yards of debris would suffice.

Brick’s presentation seemed to say the county’s plan is an overreach that will further degrade Hahamongna and the Arroyo Seco Watershed. His group filed a lawsuit in December, saying the county’s plan violates the California Environmental Quality Act and Pasadena’s General Plan and Land Use ordinances. The group raised about $34,000 in donations for legal fees through the internet site Indiegogo.

Brick juxtaposed historical slides of what used to be against those showing existing concrete channels built to protect homes against major floods.

“Charles Holder, founder of the Valley Hunt Club, wrote about how in the winter the Arroyo Seco became a literal garden where one can wander for hours at Christmas time … with trout darting at the horse’s feet,” Brick said. Some would trap bears between the Upper Arroyo Seco and Devil’s Gate for bear fighting in L.A. arenas, Brick said. Brick implied that continuation of old-school sediment-removal projects that scrape wetlands dry and severely reduce wildlife represents out-of-date thinking by the county.

“Our agency is responsible for managing the risk for those communities down stream. That goes to how much sediment you need to take out of the reservoir — the amount we’ve identified will ensure that. Otherwise, people will lose homes. The 110 Freeway will be flooded and a lot of people would die.”

Brick said the federal government should integrate flood control projects with environmental restoration. “So we don’t do one at the expense of the other,” he said.

Axt said her study will be out in summer 2016 and will include recommendations for removal of some concrete channels in the Arroyo Seco as part of a restoration alternative. She also said the county must be granted a permit from the U.S. Army Corps before it can proceed with sediment removal at Devil’s Gate.

Stone said the county applied for such a permit in the fall. Other state and local permits will be necessary, as will mitigation of any wetlands damaged or destroyed, officials said.

This story has been updated from an earlier version to include the name of the sponsor of Thursday night’s forum. Altadena Heritage sponsored the event.

San Gabriel Valley Tribune – Visit the original article