A Brief History of Altadena Land Use

by Michele Zack

The busy thoroughfare we know as Lake Avenue began as a pencil line drawn on a map dividing Rancho San Pasqual’s 14,000 acres into a grid of square-mile sections. The future Altadena occupied the top third — roughly 9 square miles — from the grant line in the north (present day Loma Alta) down to where Woodbury Road would later exist, between Arroyo Seco and Eaton Canyon.

This survey was created after California was added to the United Sates as a territory, a spoil of the Mexican American War. In accordance with Land Ordinance of 1785, land outside then-existing states must be surveyed and recorded before being sold or opened for settlement. California took the fast track to statehood in 1850 because of the discovery of gold.

Called Prospect in its upper reaches until the 1880s — Lake Avenue acquired its name because when the section line describing it was extended south, it crossed a small artificial lake built around 1800 with Indian labor at the San Gabriel Mission. One end of the land depression (now Lacey Park in San Marino) was dug out to increase its capacity from a sag pond into a reservoir. A wagon track led north from “Mission Lake” toward the mountains, and was later named Lake Avenue.

In the 1840s during California’s Mexican period, American Benjamin “Don Benito” Wilson began acquiring former mission lands including the San Pasqual and his Lake Vineyard estate; by the late 1850s he extended his holdings to build an agricultural and real estate empire including most of the future Altadena, Pasadena, South Pasadena, San Marino, and Alhambra.

Post Civil War, real estate development in Southern California took off because from 1869 it became easy to get to here via the Transcontinental Railroad. The Indiana Colony, established by Union supporters and Temperance advocates in 1874, named itself Pasadena and incorporated in 1886. It became the genteel center of a land boom soon racing out of control. The boom busted in the late 1880s, but by then Pasadena had expanded eastward to include the southern section of Lake Avenue.

Its town center was at Colorado and Fair Oaks when cardinal directions and addresses were assigned to streets. Sections of streets north of Colorado had “north” affixed to their addresses, those east of Fair Oaks “east,” and so on. Lake Avenue was extended up into the foothills to vineyards and orange groves then known simply as “The Highlands.”

Nine hundred and seventeen acres of the Highlands were formed into a subdivision named Altadena, launched in 1887 at the moment boom turned to bust. Its timing was off. Developers John and Frederick Woodbury acquired it for $5 an acre in 1882, but didn’t invest to connect to Pasadena’s rail lines and to develop water sources until 1885. A few mansions had been built or were then under construction along Mariposa Street; these, added to a few rusticated existing ranches and vineyards, were embellished into Woodbury’s vision of an upscale community that would attract Midwestern wealth as people poured West seeking new lives, opportunities, and health.

Engraved images of homes, gushing water sources, and an imagined grand hotel and a rail service yard appeared on Altadena’s promotional materials. “The business center will be started on the west side, near the Arroyo,” a newspaper article quoted a confident John Woodbury, “because the land is comparatively flat there.” This made sense; besides being flat and having water resources, Altadena’s west side was in a beeline north of Pasadena’s center at Fair Oaks and Colorado. It was the shortest, cheapest route for building a rail line; Woodbury envisioned a community of gracious homes and small farms near the Arroyo that would spread east toward Lake Avenue, following Pasadena’s land use pattern.

The Woodburys’ dreams deflated with the real estate bubble — John (the mastermind) went bankrupt, fleeing in shame back to Iowa where he remained mired in lawsuits; Captain Fred removed to a modest home in South Pasadena. Regional panic was followed by a national depression through the 1890s, and Pasadena’s population plummeted from 12,000 to 5,000.

This background is salient, because three circumstances helped Pasadena and Altadena rebound; they also established land use patterns that in Altadena, prevail today.

1) Before the bust, three north-south rail lines were built connecting booming Pasadena to sleepy Altadena, providing transportation to take advantage of new tourism and real estate up-cycles soon to come. The first two were west-side operations, one following Lincoln and veering to the arroyo and mountain camps, the other up Fair Oaks/Raymond to Mountain View Cemetery, established in 1882. The third “Highland Railroad” followed Lake Avenue. It stopped at New York Drive at first, but its franchise included rights to the top of Lake Avenue, and over to Las Flores Canyon in anticipation of a line up to Mount Wilson. Altadena thus developed as a street car suburb on a north-south axis.

2) National depression could not stop those who still had money from visiting California for health and recreation. With its grand hotels, excellent climate, capital and cultural resources, the region exerted a magnetic force on the wealthy (many of whom were sick). Most hailed from the Midwest; they fed nascent mountain tourism and health-seeking industries, and many built homes and stayed.

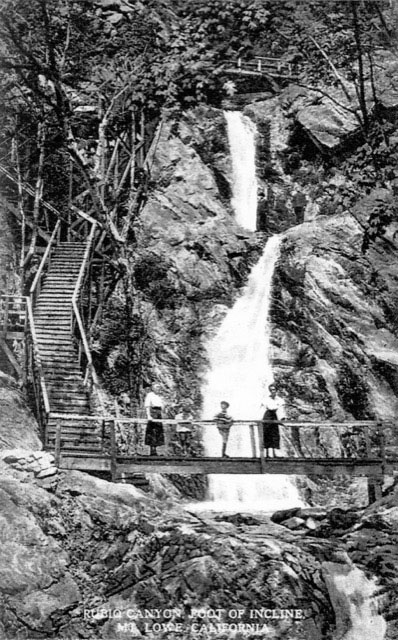

3) The most advanced engineering project in the world was the Mount Lowe Railway, launched from “Altadena Junction” — at Calaveras and Lake Avenue in 1893. Its first segment was an electric trolley running deep into Rubio Canyon, narrow, steep, and utterly wild. An instant success, the rustic Rubio Pavilion dramatically spanned the canyon below. It included a dance hall, restaurant, hotel, and wooden stairways hung with Japanese lanterns threading through fern grottos and passing over waterfalls, making nature accessible, enhanced with commercial entertainments. It was just a cheap, short trolley ride away.

Thaddeus Lowe determined Rubio Canyon would be the jumping off point for the railway’s innovative “Incline” section, which opened the Forth of July, 1895. This electric hybrid-powered project advanced technology used in San Francisco’s cable cars, and offered affluent tourists a novel alternative to the Mount Wilson Toll Road.

The Great Era of Hiking was on, and the Toll Road on the edge of Eaton Canyon was drawing thousands in conventional foot and hoof traffic on weekends by 1891 to access camps, rustic hotels, and mountain beer gardens — where Pasadena’s alcohol prohibitions were not enforced. The Mount Lowe Railway and resorts were among the first vertically integrated of tourist destinations, including through rail transport from Los Angeles and elegant hotels with extensive wine lists. Shops, restaurants, a post office, zoo, fox farm, cabins, and miles of hiking trails earned it the “Switzerland of America” moniker.

Most locals never rode the Mount Lowe Railway. However, 60,000 tourists took the thrilling Incline Rail to Echo Mountain its first year, and its popularity only grew. Visitors all poured through the sleepy highland outpost. Pasadena’s grand hotels and numerous shops benefited greatly, but Altadena had little infrastructure to attract tourist dollars. Trains from Los Angeles to the Mount Lowe railway were soon heaving up Lake, Fair Oaks, and Raymond Avenues on lines purchased from failed predecessors. All converged at Altadena Junction, which became a transport hub for mountain tourism — both rail and equestrian. The Tally Ho Livery Stable catered to those renting horses and carriages to access Mount Wilson camps via the Toll Road. Inevitably some, both affluent and middle-class, stayed and bought real estate.

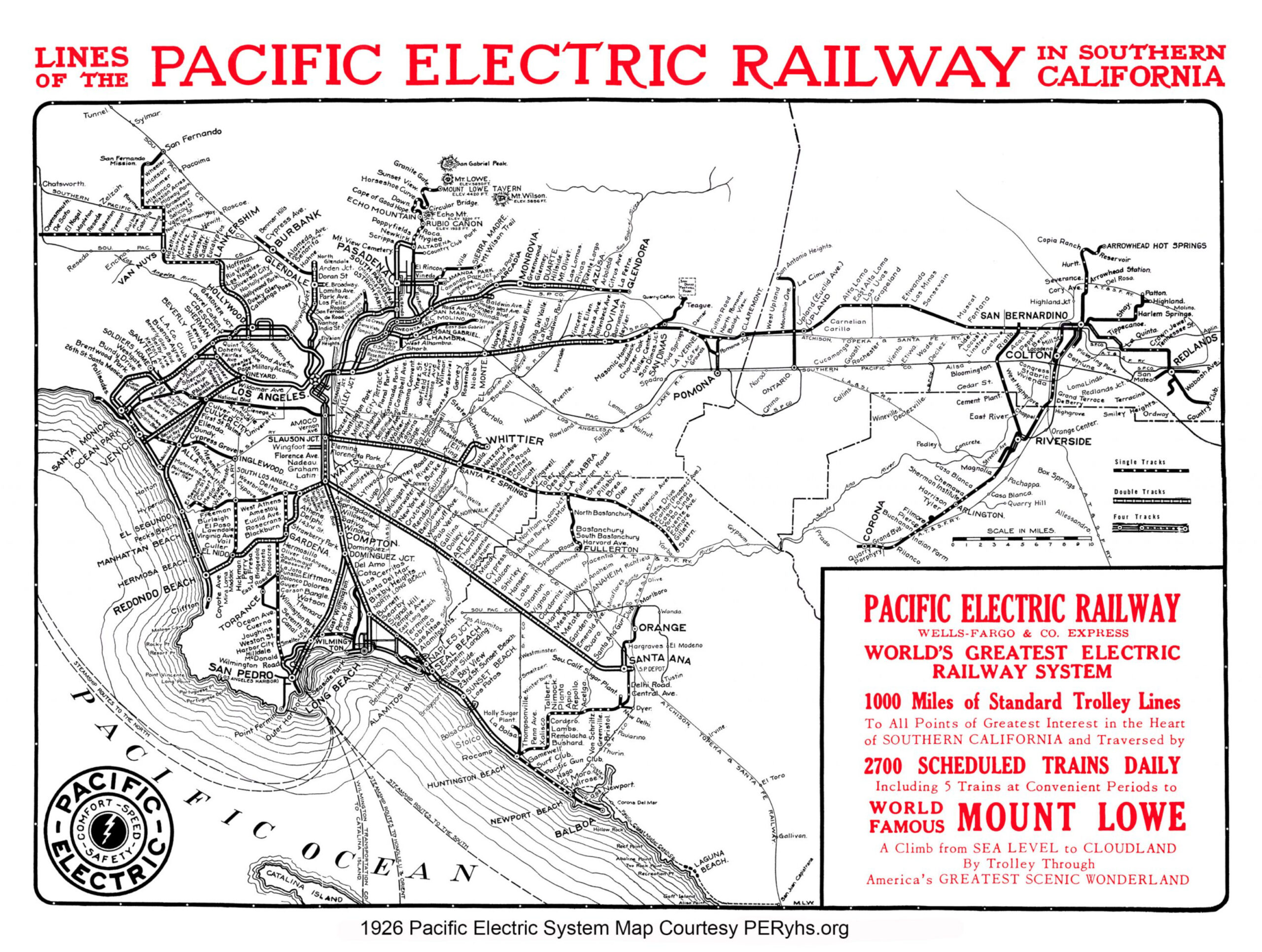

The Junction’s stables and beautiful brick power house at Calaveras on Lake Avenue remind us of a time before transportation was ruled by the automobile. In 1903, a second Altadena hub developed a half mile north at Lake and Mariposa, when Henry Huntington established his Pacific Electric Railway and bought out the bankrupted Thaddeus Lowe. He added an east-west rail “Dinkie” (small gauge) line across Mariposa from Fair Oaks to Lake serving tourists, workers, domestics, and new homeowners. Huntington made his money selling real estate, not trolley tickets. By 1912, he’d gobbled up all smaller, less profitable lines to make Pacific Electric the largest inter-urban rail system in the world connecting 50 communities in four counties over 1,164 miles of track. Altadena’s fate as a north-south trolley car suburb was thus cemented: most people didn’t yet have automobiles — the closer you lived to the train, the better. As home ownership began growing, modest neighborhoods cozied up to trolley lines.

Small businesses began sprouting at the relatively flat intersection of Mariposa and Lake. La Mariposa Hotel opened in 1907 as Altadena’s first commercial building not directly tied to transportation. In the Progressive Era preceding the Roaring ‘20s, Altadenans also began debating (and rejecting) the idea of incorporating as a city. Many surrounding communities had taken this crucial step to plan, and to control commercial and residential development. Only cities can raise taxes and enact local ordinances.

The area around Lake and Mariposa was called “the heart of Altadena’s business district.” Our unincorporated town’s population grew faster than any where else in L.A. County in the 1920s — from 3,000 to nearly 20,000 people in under a decade. The arrival of so many without established shopping habits in Pasadena ushered in Altadena’s first golden age of commercial development on Lake, Fair Oaks, and Lincoln Avenues. New businesses proliferated as housing — affordable, median, and luxurious — replaced farms and orchards.

Extensions of Altadena Drive and New York Drive east of Lake Avenue, as well as a Dinkie line along Mendocino to the Country Club, (established in 1911), opened East Altadena for home building. Washington Boulevard between Hill and Altadena Drive, and a node at Allen and New York, also began developing commercially. Country Club Park, a subdivision of one-acre-plus lots on 500 acres of the old Allen Ranch, began infilling Altadena’s last open expanse, shifting exclusive housing east from Mariposa Street’s “Millionaire’s Row.” Altadena farmers, dairies, and commercial nurseries continued favoring west Altadena because of superior water resources and soil.

Westside land was also cheaper; besides agriculturally-inclined buyers it attracted modest and middle income home builders. Elisha P. Janes built close to 200 affordable Tudor-style cottages between Marengo and Lincoln, acting as financier, builder, landscaper, and sales agent. Bankruptcy forced him out in the panic of 1927 preceding the Great Depression, however the division of former agricultural parcels into smaller lots continued, creating new middle-class neighborhoods and encouraging commercial uses along with residential on Fair Oaks and Lincoln.

Altadena’s many advantages explain its phenomenal growth in the 1920s, and beyond. With natural beauty and mountain views, the community enjoyed an extraordinary range of real estate options — and excellent transportation links to Pasadena and Los Angeles. That it remained unincorporated also meant minimal enforcement of Prohibition. Webster’s Pharmacy on North Lake was the only place in the San Gabriel Valley where one could fill a prescription for alcohol, and liquor was available at two popular destinations, the Marcell Inn at the top of Lincoln, and the private Altadena Country Club east of Lake Avenue, as well as at smaller establishments along Lincoln and in the mountains.

Automobile ownership skyrocketed and commercial areas developed in the 1920s, but Altadena remained as it began, a streetcar suburb without a civic core. Its shopping areas were long, skinny affairs — mostly along steep north-south grades. No dominant business zone or town center developed, with the exception Lake Avenue centered at Mariposa. Residential builders snuggled up to small commercial areas and nodes with convenient, modest housing. Three factors reinforced the pattern: Altadena’s abundance of good public transportation; sufficient still-open land; and, third, a total lack of planning as an unincorporated community of Los Angeles County.

Click map to enlarge

Once this pattern was established, without provision for commercial expansion or parking, it continued. No agency focused on planning, and people liked living near shops. About once a decade from the turn of the century through the 1960s, local cityhood campaigns failed to convince a majority of Altadenans that projected benefits — coming as they would with taxes, budgets, politicians and bureaucrats — outweighed costs.

Altadena’s landmark institutions were almost all on or within a block of Lake Avenue: Farnsworth Park, the William Davies Recreation Building, original and new Sheriff’s stations, First Federal Savings and Loan Association of Altadena, Altadena Library, Eliot Junior High School, Scripps Home for the Aged, and St Elizabeth Church. Including schools in other parts of town, a total of six were built during or significantly expanded within 10 years of the Depression. Churches from Pasadena were also attracted by inexpensive land along Lincoln.

A major loss during this era, closure of the Mount Lowe Railroad in 1936 due to fire, and an addition, the opening of the Los Angeles Crest Highway in the 1940s, hinted at changes to come. One incorporation bid after another failed, as Pasadena nibbled away at the shrinking Altadena in 37 separate “bites” as that city increased its tax base. One can imagine people thinking regarding cityhood: with so much civic and commercial development, who wants another layer of government telling us what to do and taxing us?

Post-World-War-II, tremendous demand for housing plus easy credit from new FDIC loans and the GI Bill, drove the largest expansion of homeownership in US history. Altadena, still with open land, was attractive to builders. From 1946 through the early 1960s, almost every spare scrap, most on the west side (including the Meadows, Altadena’s first integrated neighborhood and Floricita Farms on the Arroyo), but also in east-side Presidents Street developments, filled with new “ranch” houses. (See box on Racial Change below.) The last agricultural land was subdivided, along with old estates such as those of Zane Grey, Col. Green, and Scripps families. Absent planning or much oversight by Los Angeles County, the quality of building, subdivisions, and public infrastructure was uneven.

Altadena grew to over 46,000 people in the 1950s as baby boomers swelled the population — compared to 43,000 today. The modern community has since evolved and gone through significant social, racial, and cultural changes — but its land use patterns were set in the streetcar era.

The current era of climate change and unsustainable urban sprawl is the new driver of land use policies: statewide regulations are encouraging infill, and discouraging building in fire-prone foothills. Insurance companies and state regulations are combining to make living in Altadena more expensive — but also curbing hillside development.

This article was adapted and condensed from an earlier paper prepared for an Altadena Heritage committee studying commercial and residential land use.

Racial Change Over Time

Just as a pencil line drawn on a map of California in the 1850’s influenced the future of where Lake Avenue would be built — another pencil line drawn from the 1930s-60s denied or limited financial services, such as home loans in certain neighborhoods. It was called “red-lining”, and contributed to an east-west polarization in housing along racial lines in Altadena in the 1960s and 70s. This important story belongs more to the town’s social and cultural history (see Altadena: Between Wilderness and City, 2004, pp 170-187) than in a brief overview on land use. However, because dramatic changes occurred in a short period, it would be an oversight not to summarize how demographic shifts along with red-lining affected Altadena’s residential and commercial land use, and to provide an update.

In 1960, Altadena was overwhelming (95%) white, the majority of its neighborhoods covered with by-then-defunct racial covenants. For a variety of Pasadena-linked causes including urban renewal, turnover of housing stock, and freeway construction — combined with larger events such as the Civil Rights Movement, Watts Riots, Vietnam War, and political assassinations — many whites began leaving Altadena, especially West Altadena. By 1970, the town was 68 percent white, while the next census in 1980 counted the population as 49% white. This share remained fairly stable for the next 20 years: in 2000 the white population was 47%. In the same period the share of Black residents went from under 4% in 1960, to 27% in 1970, to 43 percent in 1980, to 39% in 1990, to 31% in 2000. Such convulsive racial change in housing spilled over to affect commercial activity in the most impacted areas, causing an overall down cycle in real estate values for a time. Bargains were to be found in homes all over Altadena.

In the years since, Altadena has followed the national trend of becoming an increasingly diverse suburb, but with an unusually stable population of around 43,000. It is now considered an affluent area (under 9% poverty rate, compared with 14% countywide) and a strong homeownership rate of over 70%. This compares with 42% in Pasadena, 56% statewide, and 65% nationally. Today’s census broken down by race: whites, 53.2%: blacks, 19.6%; other race, 14.3%; two or more races, 6.94%; Asian, 5.16%; Native American, .6%; and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, .1%. Altadena’s diversity and wide range of housing stock attracts new homeowners of all stripes.

As in 1980, more Black residents live west of Lake Avenue in 2023, but today’s diverse Altadena neighborhoods are all integrated. Racial housing patterns shift slowly or quickly along with demographics, but no summary of residential land use would be complete without a word about the real estate industry’s role as the homebuyer’s chief consultant. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Fair Housing Act of 1968 legally dismantled the “Red-lining” of neighborhoods, it continued informally, practiced when agents steer clients to this or that community, or side of town based on judgements about class and race, and needs such as educating children. This has decreased dramatically since the 1960s and 70s, when many agents made Lake Avenue a dividing line — not showing Black clients properties to the east of it, or white clients homes to the west of it. Today in Altadena, we hear more complaints from long-time residents about gentrification than integration, and we’re once again in a real estate upcycle. No more bargains, for now.