A Short History of Fire and Fire Protection in Altadena

By Mike Manning

The following story, somewhat abridged here, appeared in the January 1994 edition of “Peaks at Altadena”, a monthly news magazine put out by the Manning family, Mike, Sean, Julie and Stacy. It had no byline, but we tracked down Sean who confirmed that Mike wrote this piece shortly after the October 1993 fire in the hills above Altadena. Mike Manning was a founding member of Altadena Heritage and active in community affairs for many years.

To see our hillsides ablaze as they were on October 27 [1993] was awesome yet frightening. It was no different over 100 years ago. Our forests and hillsides here in the San Gabriels have been the topic of fire discussion since the late 1880s. Fires raged out of control in those days and for the most part, except for occasional lightening strikes, humans were the cause. There were the careless homesteaders and reckless campers, but even sheep ranchers used to indiscriminately set wooded areas on fire in order to clear pasture land for grazing. What excess the blazes burned was of no concern to them.

It did, however, concern civic leaders of major metropolitan Los Angeles and surrounding farm communities. Valuable watershed was either destroyed or badly polluted by forest fires. The forest lands of San Gabriel were public lands used on a first-come-first-served-anything-goes basis. It was an Altadena rancher, Abbott Kinney, who brought about the development of national forest reserves. Kinney was the first chairman of the California State Board of Forestry. He developed Kinneloa Estates, and as a naturalist and conservationist as well as a developer, he experimented with livestock, hillside forestation, and watershed management in an attempt to study how all these properties could be managed together.

Kinney helped to effect passage of the Forest Reserve Act of 1891. With this President Benjamin Harrison could create forest reserves under the auspices of the Department of the Interior, and the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve was established in 1892. In theory these forest reserves were protected by law. In actuality they were not policed and were subject to continued human abuse. But in 1896, devastating forest fires, blackened great areas of forest in he San Gabriels and San Bernardino and led to public outcry for a national policy of forest policing.

Colonel B.F. Allen helped establish a mounted patrol on the reserves, and in July of 1898 was allowed to hire temporary help during the fire season to help patrol the forests and prevent or suppress fires The duties of these first rangers were burdensome and their patrol areas were vast. As years went by, the national Forest Service developed into a large supportive network of federal agents protecting our forest reserves.

To help with reforestation following forest fires, the government leased property in Henninger Flats above Altadena where experiments with reseeding a variety of pine trees was carried out by Pasadena conservationist Theodore P. Lukens, later referred to as the Father of Forestry.

For the first 40 years of Altadena’s existence there was virtually no civil fire protection service, volunteer or otherwise. Burning structures waited for Pasadena units to arrive from miles away and invariably burned uncontrollably. By 1922, the Altadena Citizens Association began a campaign to develop a fire protection district with the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. A state law was passed in January 1923 providing funds to develop such districts in the unincorporated parts of the county, and Altadena voters passed its assessment district in March of that year.

A 20 man forestry unit was established in 1924 under direction of William D. Davies, for whom the Davies Building in Farnsworth park is named. With cooperation of the three Altadena water companies and the Forest Service, Altadena hillside protection was well in hand.

During 1925 one hundred fire hydrants were hooked up throughout Altadena, and insurance rates were dramatically reduced. By 1927 200 hydrants had been installed and in July of that year, Station No. 12 on Lincoln below Harriet was completed. At this point, Altadena has as good a fire department as any city.

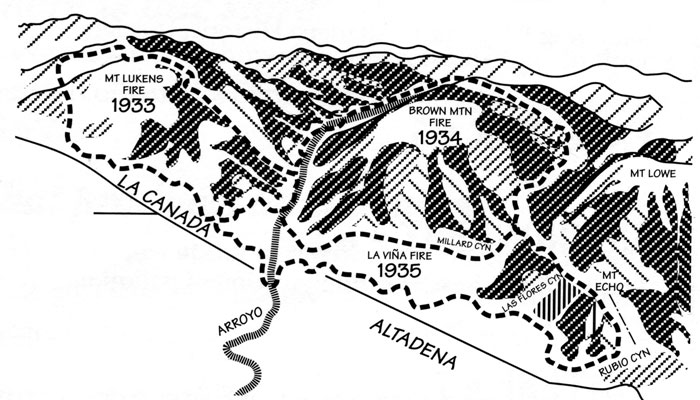

In three successive years from 1933 adjacent sections of the foothills were blackened by fire. The 1933 Mt. Lukens fire destroyed watershed over the Tujunga and La Crescenta areas. In 1934, the Brown Mountain fire burned valuable watershed of the Millard Canyon and Arroyo Seco. Assistance from the CCC camps brought these fires under control. On October 23, 1935, fire broke out in the Las Flores Canyon above Altadena. Santa Ana winds blew the blaze over to La Viña Sanitarium and destroyed it. This fire caused more loss of property than the fires of the two preceding years. Nevertheless, the fire fighting resources of Altadena were sufficient enough to deal with the conflagration and the fire was brought under control within a day.

Fire has long been referred to as the “Mother of Floods.” The secondary fear of fire-ravaged hillsides is flooding and mud slides. A prime example of flood following fire occurred after the Pin Canyon fire of September 1979. Rubio Canyon in particular was severely burned. As misfortune would have it, rains of the 1980 season, which measured upwards of 11 inches in 24 hours at higher elevations, caused mud and debris to fill the flood basin at the mouth of Rubio within a matter of minutes. Several houses on Gooseberry Lane, Sunny Oaks Circle, Altadena Drive and Braeburn were flooded. Some homes were actually rocked loose from their foundations. Evidence of flooding was visible near the golf course at Winrock and Morada, and as far south as Washington Boulevard. For weeks on end, at a round-the-clock pace, the County Flood Control District trucked mud from the debris basin to avoid further catastrophe from the next rain storm.