A Short History of La Viña

By Val Zavala

Tuberculosis has killed more people than any other disease in the history of humankind. (Let that sink in.)

Its bacterium lodges in the lungs, creating pustules that cause bloody coughs, hacking, and lung pain. Victims waste away or are consumed. Thus, TB was dubbed “consumption.”

Some strains killed in a matter of days; this was called galloping consumption. Other patients survived years, seemingly cured. Still others lived long but debilitated lives. The elite were not spared. Lord Bryon, Anton Chekov, King Edward VI, Frederic Chopin and three of the Bronte sisters all died of “the wasting disease.” In the first half of the 19th century so many poets and writers died of it that a pervasive belief was that intelligent and sensitive people were particularly vulnerable.

But from the mid-1850s, TB grew into the major cause of all adult death in US cities, fueled by crowded and unsanitary living and working conditions precipitated by the Industrial Revolution. The outbreak lasted for decades and brought health seekers west. A TB hospital was built at the north end of Lincoln Avenue on the site of a vineyard owned by the Giddings family — the same Giddings who established Mountain View Cemetery 30 years earlier. In 1911 “La Viña Sanatorium” opened, and for more than six decades offered care and sometimes a cure for 50,000 tuberculosis patients.

A driving force behind La Viña was Dr. Henry Stehman, a physician from Chicago who barely survived TB himself. In 1899 he moved to Pasadena, long touted as a paradise for recovering consumptives — just as isolation became understood as the best way to slow infection rates. Once recovered, the modest doctor quickly turned his attention to treating other

TB patients.

Dr. Stehman met Pasadena’s prominent philanthropic leader S. Hazard Halstead, and together (with help from Norman Bridge, a fellow physician from Chicago who had recovered from TB in Sierra Madre), spearheaded fundraising for construction of La Viña Sanatorium. It opened in 1909 with 17 bungalows. Two years later thirty-six more rooms opened.

In addition to isolation to halt its spread, TB treatments offered were ones then available: clean air, rest, and a healthy diet. La Viña was one of dozens of sanatoria serving thousands of TB “pioneers” lured to southern California to escape the cold, crowded, and unsanitary cities in the east and Midwest. At least five TB sanatoria were located in Altadena in the new century, with La Viña being the largest and longest-lived.

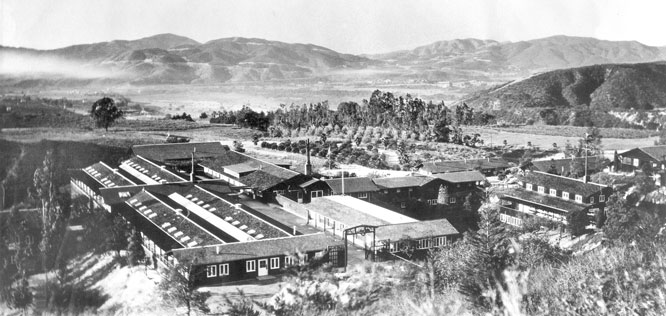

La Viña Sanitorium in the 1920s.

Historian Cecilia Rasmussen of the LA Times described life at La Viña. “There were four horses, chickens, turkeys, cattle, orange and grapefruit trees, vineyards, and its own post office. Income from selling the grapes, eggs and milk helped defray expenses and feed the patients. The income from grapes, however, dropped each year as a rapidly expanding deer herd in the area ate more of the harvest. As part of their treatment, some patients helped lay sidewalks and assisted in gardening to help strengthen their muscles. Others were encouraged to try arts and crafts, with the hope that they would produce articles that they could sell themselves. The average cost of care was $1.41 per day.”

How successful was the regimen? Certainly, escaping contagious crowded settings and adopting a healthy lifestyle helped many recover. Nevertheless, TB mortality was high in 1900 — 194 per 100,000 patients. Today, with testing and antibiotics, TB is rare and manageable. The American Lung Association reports 0.2 deaths per 100,000 Americans.

La Viña offered hope and healing. Its patients were often indigent or of limited means, but half the cost of care was covered by donations. In the beginning Dr. Stehman worked without pay.

In 1935 a fire swept through Las Flores Canyon and the sanatorium. Patient housing was all destroyed and only the administration building survived. Insurance paid $69,000 to rebuild; this was augmented by donations of $178,000 for a new 51-bed hospital. It was designed by renowned architect Myron Hunt, who also designed Altadena’s Preventorium and Five Acres institutions.

The new sanatorium’s single and double rooms were well-ventilated with porches facing an inner courtyard, and windows on both sides. It was among California’s first structures designed for seismic safety.

From 1945, the property began housing a research center named for Charles Cook Hastings, who died of tuberculosis. His son, Charles Henry Hastings, opened a facility where 20 tubercular veterans were given free treatment and care. Just as an antibiotic cocktail was beginning to control TB, research there finally investigated effects of nutrition on recovery. This had long, but anecdotally, believed to be of import — and sparked the beginning of the health food industry. Science magazine reported, “Objective nutrition tests on the blood and bio-microscopic exam of the eyes, tongue and gums will be part of the routine exam of the subjects all of whom will receive a good standard sanatorium diet and one half being given food supplements. Progress of the disease in both groups will then be carefully compared.”

Rendering of La Viña’s redesign after 1936 fire. Photo courtesy Paul Ayres.

After 18 years the research center merged with USC and the facility was shuttered. As TB treatment evolved, purpose-built facilities dedicated to it were no longer needed. By the 1980’s, the patient count dwindled as therapy had become home isolation with antibiotics. Eventually it merged with Pasadena’s Huntington Hospital. A $20 million “La Viña Wing” opened, commemorating the earlier institution.

As for La Viña’s 160 plus acres, they were sold to a developer. (The history of how it became the gated home community of the same name is well-told in Michele Zack’s Altadena Between Wilderness and City.) Suffice to say, for more than a decade the property was the center of conflict that split Altadena into factions. Among controversial proposals was one by Scientologists to build an archive for the writings and documents of founder L. Ron Hubbard. Many Altadenans pushed for the chaparral land to be left as a trail-crossed nature preserve, but in the end, housing prevailed. In 1993 construction of the 272-home development began. Realtor Steve Haussler recalls that they “scraped the ground bare with massive earth movers. The shock was mind-bending. But then they built houses and planted trees. Now it looks normal.” Home sales began in 1998. “The economy had recovered from the recession. People started looking at Altadena and a bunch of Altadenans moved to La Viña, too,” says Haussler.

As for Dr. Henry Stehman — the dedicated physician who helped contain the disease dubbed “Captain of Death” — he died at the age of 66 in 1918, and is buried in Mountain View Cemetery. His fellow-doctor and friend, Norman Bridge, wrote a published remembrance describing Dr. Stehman as “a great man whose career as citizen, physician, and philanthropist was unique… He was a man of vision and whatever he undertook he did. La Viña was his greatest work… It was his ambition to make a haven for at least a few of the many consumptives who walk the streets as long as they can – and walk in loneliness. And this he nobly did.”