Interpretive Signs Installed

The Owen Brown Gravesite Committee installed an interpretive sign to explain the significance of the monument as well as an interpretive sign to commemorate an even earlier resident of the the area, Robert Owens. Here is our website presentation of the two signs.

An Abolitionist Comes West

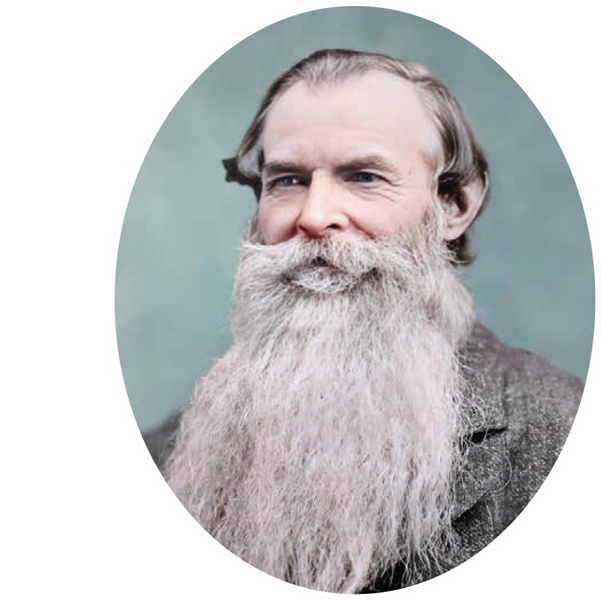

wen Brown is buried at the top of “Little Round Top,” named for the heroic stand by Union troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. He and his brother Jason lived nearby on land they homesteaded in the 1880s. He was the last survivor of the 1859 raid on the U.S. Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, led by his father, abolitionist John Brown, who hoped to spark an insurrection to end American slavery.

wen Brown is buried at the top of “Little Round Top,” named for the heroic stand by Union troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. He and his brother Jason lived nearby on land they homesteaded in the 1880s. He was the last survivor of the 1859 raid on the U.S. Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, led by his father, abolitionist John Brown, who hoped to spark an insurrection to end American slavery.

Later, this raid was called the first battle of the Civil War. Ten raiders, including two of Owen’s brothers, were killed in action. John Brown was among seven captured, tried, and hanged for treason.

The granite headstone was added to Owen’s grave in 1898 by Horatio N. Rust. On this occasion Rust said, “His service to his fellow man is a more lasting memorial… He gave the best years of his life…to uphold the cause of human freedom.”

Owen and Jason Brown outside their cabin, looking south. Little roundtop on the right.

But Why to Pasadena?

The funeral procession of Owen Brown on Colorado Street looking east from Raymond Avenue in Pasadena, 1889

fter living more than 20 years as a fugitive from the law for his role in the Harpers Ferry raid, Owen Brown, his brother Jason, their sister Ruth and her husband Henry Thompson moved to Pasadena, founded shortly after the Civil War by Union Army veterans and supporters. Many had been abolitionists who shared the Browns’ progressive and temperance-minded beliefs. Admirers including locals, visiting Union veterans, and former slaves and their descendants trekked to Owen’s remote cabin, wanting to shake his hand. Since Owen’s death in 1889, this grave has been a pilgrimage site and memorial to the sacrifices of the Civil War and the battle to end slavery.

fter living more than 20 years as a fugitive from the law for his role in the Harpers Ferry raid, Owen Brown, his brother Jason, their sister Ruth and her husband Henry Thompson moved to Pasadena, founded shortly after the Civil War by Union Army veterans and supporters. Many had been abolitionists who shared the Browns’ progressive and temperance-minded beliefs. Admirers including locals, visiting Union veterans, and former slaves and their descendants trekked to Owen’s remote cabin, wanting to shake his hand. Since Owen’s death in 1889, this grave has been a pilgrimage site and memorial to the sacrifices of the Civil War and the battle to end slavery.

The funeral procession of Owen Brown on Colorado Street looking east from Raymond Avenue in Pasadena, 1889

How El Prieto Canyon Got Its Name

No photos exist of Robert Owens (died 1865). This image is based on photos of his grandson.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason (1818–1891)

Colorized photo

El Prieto Canyon

In Spanish El Prieto” refers to the dark one — and this scenic place was named for Robert Owens. He settled here in the early 1850s, after being born into slavery and through years of hard labor saving enough to buy his freedom. He left Texas for California, which had recently entered the Union as a free state, but with a history of unfree labor. Native Americans and people of African or Chinese descent had few rights. Despite these obstacles, Owens dealt in lumber and supplied building materials to the US Army, earning enough to buy the freedom of his wife Winnie and their children, who joined him in the canyon. His success allowed the family to move to Los Angeles, where he opened a livery stable downtown with John Hall, another African American. He built a real estate portfolio and eventually became wealthy. The Owens’ home became a center of the African-American community, where early religious meetings and business gatherings took place.

Freeing Biddy Mason

Robert Owens is linked with another famous Angelino: Biddy Mason. Robert Smith brought Mason from Utah to a Mormon community in San Bernardino. Smith held her and others in bondage for nearly five years after California outlawed slavery.

Finally, in late 1855, Robert Owens and his son Charles helped to apprehend Smith, who was challenged in court, resulting in Mason and 13 others winning freedom. Mason went on to a successful career in midwifery, nursing, real estate, and philanthropy. She used her substantial wealth to help others in need, including the hospitalized and incarcerated. Charles Owens married Mason’s daughter Ellen, and the two became prominent in the Los Angeles African-American community.

Photo: Erik Hillard