Owen Brown in Altadena California

Jason and Owen Brown Homestead

The Brown Boys Rancho looking to the south with Little Round Top, where Owen Brown would later be buried, in the background.

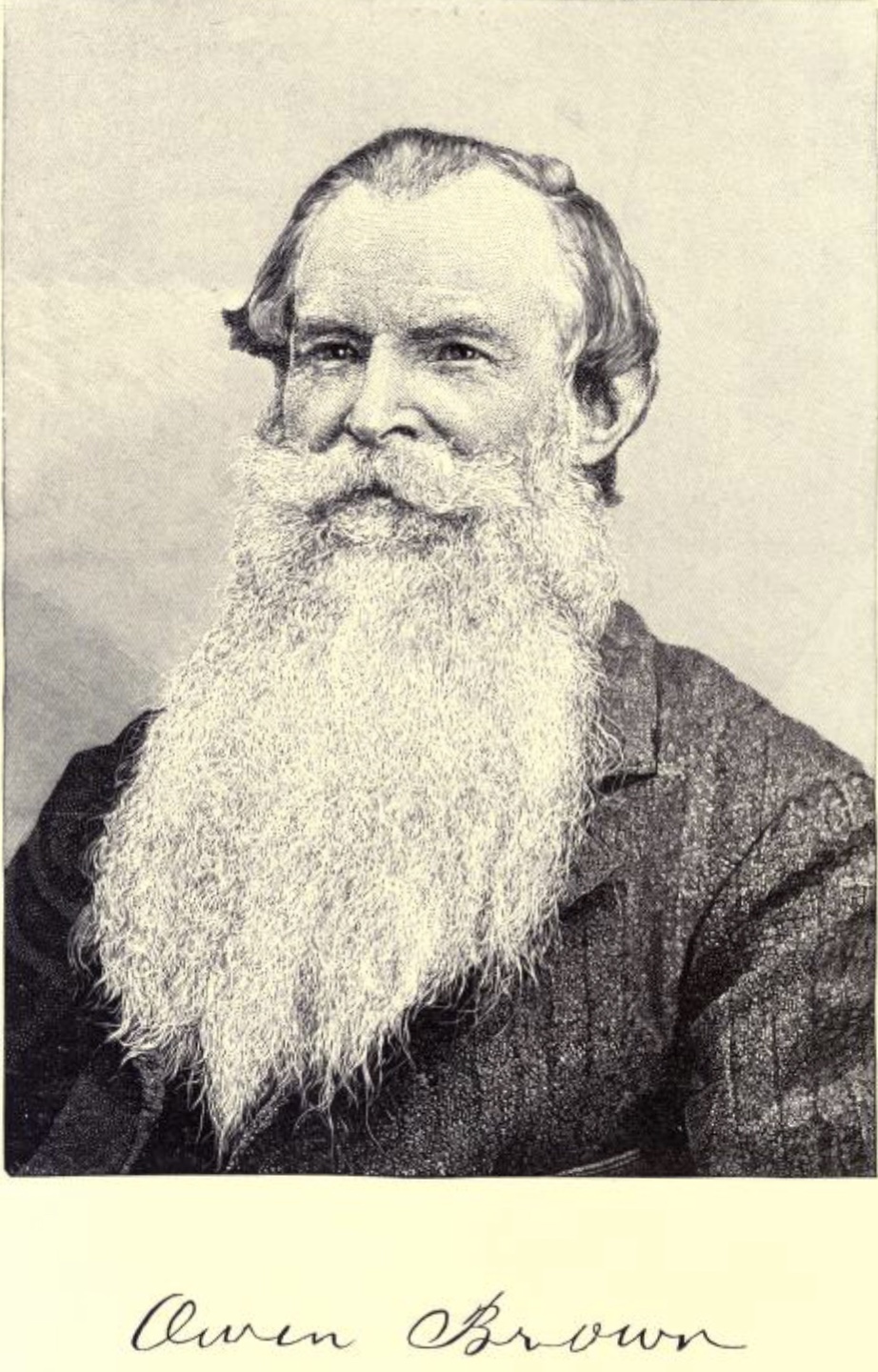

Owen Brown History

Click any image to isolate/enlarge

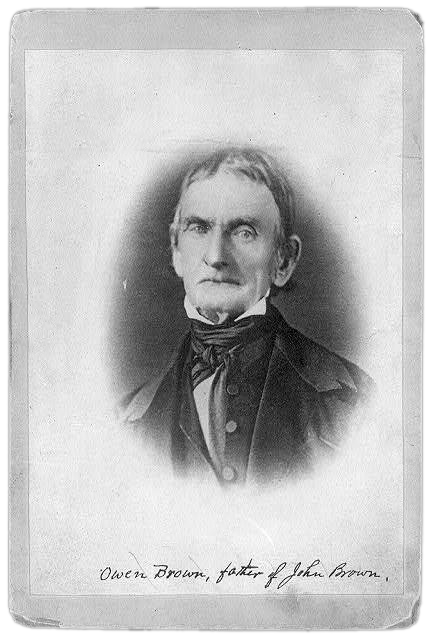

Owen Brown was born November 8, 1824, in Hudson, Ohio, to John Brown and Dianthe Lusk, their fourth child. He was named after John Brown’s father, an early abolitionist and pioneer of Ohio. Owen’s mother later died while giving birth to a seventh sibling. John Brown remarried and fathered thirteen more children with his second wife, Mary Ann Brown.

Owen grew up in his family’s tannery, located in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, which camouflaged facilities to help people escape from slavery. Although tall and strapping, a childhood accident left him with a withered right arm. The family moved to Ohio, where John Brown became more militant and outspoken in opposition to slavery after the notorious November 1837 lynching of Elijah Parish Lovejoy for publishing an abolitionist newspaper. John Brown stated publicly, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!”

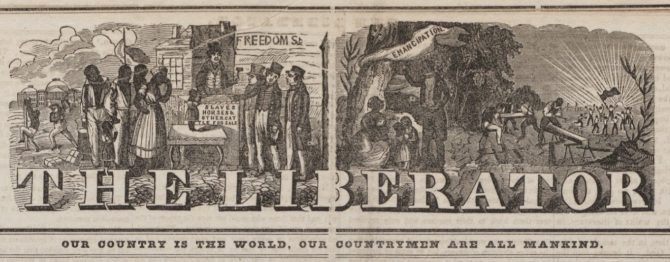

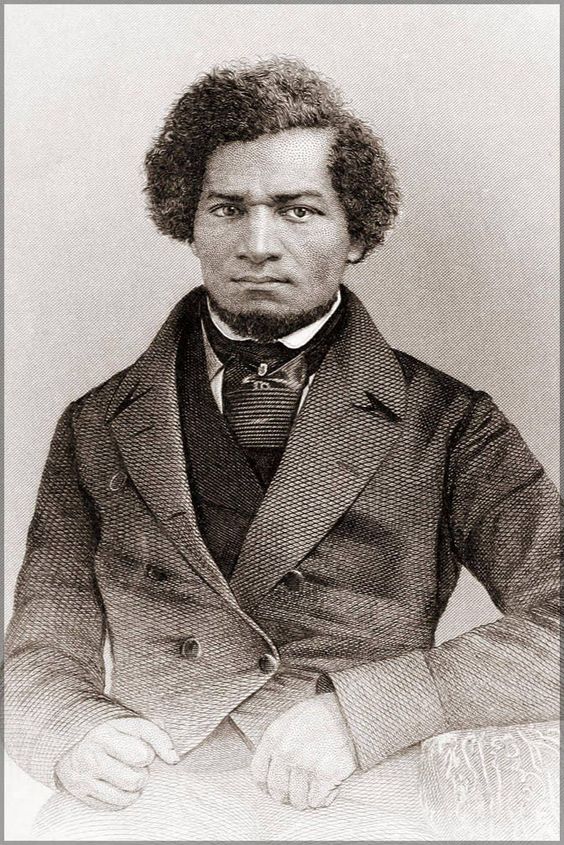

The Brown family relocated to Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1846, the heart of abolitionist activism, where he became involved with William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator, and former slaves Frederic Douglass and Sojourner Truth. Douglass would later write, “From this night spent with John Brown in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1847, while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition.”

In 1848 Brown took his family to North Elba, New York, where they could support themselves while continuing to assist with escapes on the “underground railroad.”

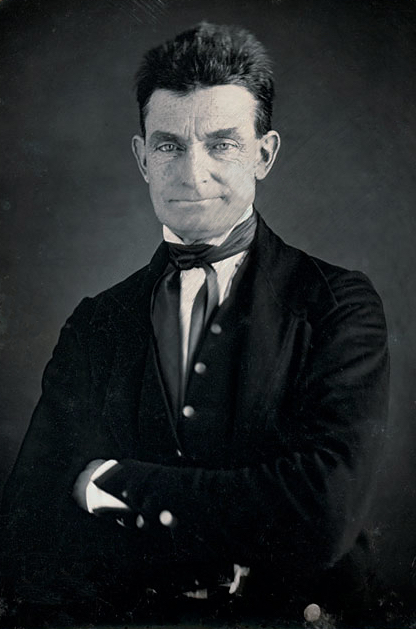

Enraged by the reactionary Kansas-Nebraska Act that would allow new slave states north of the 36th parallel, however, in 1855 John Brown followed his sons John, Jr., Jason, Owen, Frederick, Salmon and Oliver, along with his daughter Ruth’s husband Henry Thompson to the Kansas territory, to oppose Southern mercenaries intent on bringing Kansas into the Union as a slave state. Owen was then widely viewed as the son most like his father in temperament, politics and appearance, and would become his father’s loyal lieutenant.

Fighting broke out in Spring of 1856, leading to a national debate over “Bleeding Kansas,” a trigger for the development of the anti-slavery (but not abolitionist) Republican Party. After denouncing southern slave owners for backing “border ruffians” who sacked Lawrence, Kansas, the center of anti-slavery activity, destroying both its abolitionist newspapers, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was beaten nearly to death on the Senate floor by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks.

To retaliate for Lawrence and the “caning of Sumner,” on the evening of May 24, John Brown’s band of abolitionists killed five “professional slave hunters and militant pro-slavery” men in Potawattomie, Kansas. Owen is said to have put one to death personally.

Fighting continued through the summer, leading to the death of Frederick on August 30 before a truce was arranged. Largely due to the determination and sacrifices of Brown’s “army,” Kansas established itself as a free territory in 1858.

The lesson that John Brown took from Kansas, however, was that only an armed slave insurrection in the heart of the South could put an end to slavery. He and Owen returned to Massachusetts to raise money covertly from wealthy supporters, including those who later became known as “the Secret Six.” Some abolitionists, including Garrison and Douglass, were ambivalent or opposed to Brown’s proposed violence, while others, including Harriet Tubman, whom John Brown always addressed as “General,” actively supported him.

To implement the plan in the fall of 1859, John Brown’s group stocked the Kennedy Farmhouse, located in Sharpsburg, Maryland, with weapons and ammunition. Their target was the United States Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. There, 100,000 rifles were stored along with ammunition.

On October 16, John Brown led 21 men, including sons Oliver and Watson, across the bridge into Harpers Ferry, while Owen and four others remained on the other side with supplies and animals. After initial success in taking over the armory, the raid quickly degenerated into a fiasco, and John Brown was trapped. Realizing their failure, Owen led a daring escape through the backwoods of Maryland and Pennsylvania, unable to show his head.

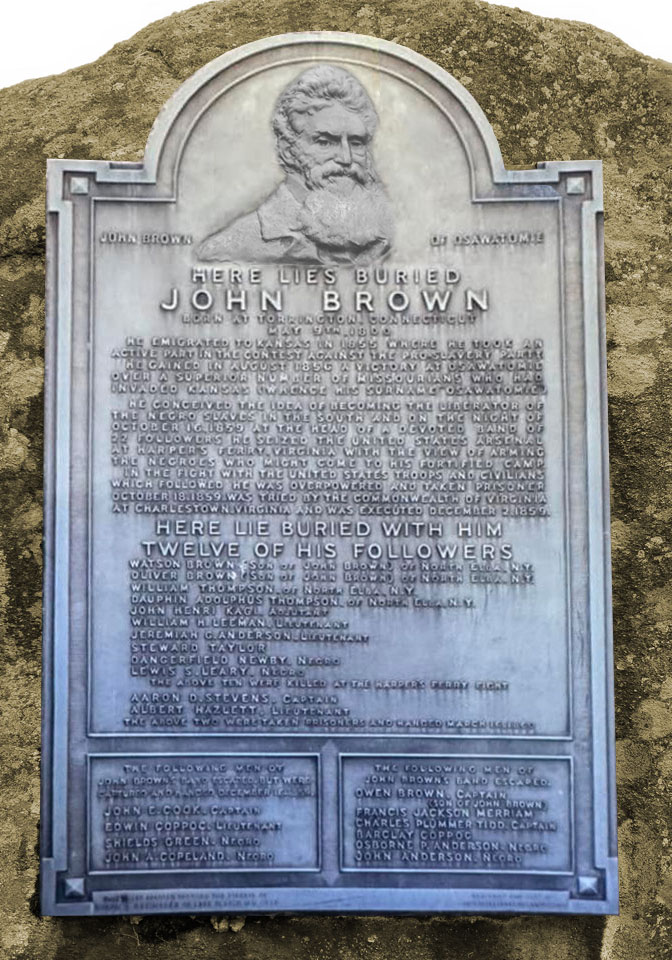

Gravemarker – North Elba, New York

Written on the Plaque

John Brown of Osawatomie

Here Lies Buried

JOHN BROWN

BORN AT TORRINGTON CONNECTICUT ON MAY 9TH 1800

He emigrated to Kansas in 1855 where he he took an active part in the context against the pro-slavery party. He gained in august 1856 a victory at Osawatomie over a superior number of Missourians who had invaded Kansas (Whence his surname “Osawatomie”)

He conceived the idea of becoming the liberator of the negro slaves in the south and on the night of October 16, 1859 at the head of a devoted band of 22 followers he seized the United States Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia with the view of arming the negroes who might come to his fortified camp. In the fight with the United States Troops and Civilians which followed he was overpowered and taken prisoner October 18, 1859 was trialed by the commonwealth of Virginia. At Charlestown, Virginia and was executed December 2, 1859.

HERE LIE BURIED WITH HIM TWELVE OF HIS FOLLOWERS

Watson Brown (Son of John Bow) of North Elba, NY

Oliver Brown (Son of John Bow) of North Elba, NY

William Thompson of North Elba, NY

Dauphin Adolphus Thompson of North Elba, NY

John Hernai Kagi. Adjutant

William H. Leeman. Leutnant

Jeremiah D. Anderson. Lieutenant

Steward Taylor

Dangerfield Newby. Negro

Lewis S. Leary. Negro

The above ten were killed at the Harpers Ferry Fight

Aaron D. Stevens. Captain

Albert Hazlett. Lieutenant

The above two were taken prisoner and hanged march 15, 1866

On October 18, John Brown surrendered to military forces that included U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee. Sons Oliver and Watson had been killed in action. Brown and his surviving comrades were tried and convicted of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States.

Before he died, John Brown declared, “If it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments—I submit; so let it be done!”

Owen avoided capture and found refuge with his oldest brother, John Brown, Jr., in Ohio, eventually settling on Gibraltar Island in Lake Erie, near Put-In-Bay outside of Cleveland. Owen Brown’s harrowing tale of his escape was published in The Atlantic Monthly of March 1874. Mark Twain himself commented, “Three different times I tried to read it but was frightened off each time before I could finish. The tale was so vivid and so real that I seemed to be living those adventures myself and sharing their intolerable perils.”

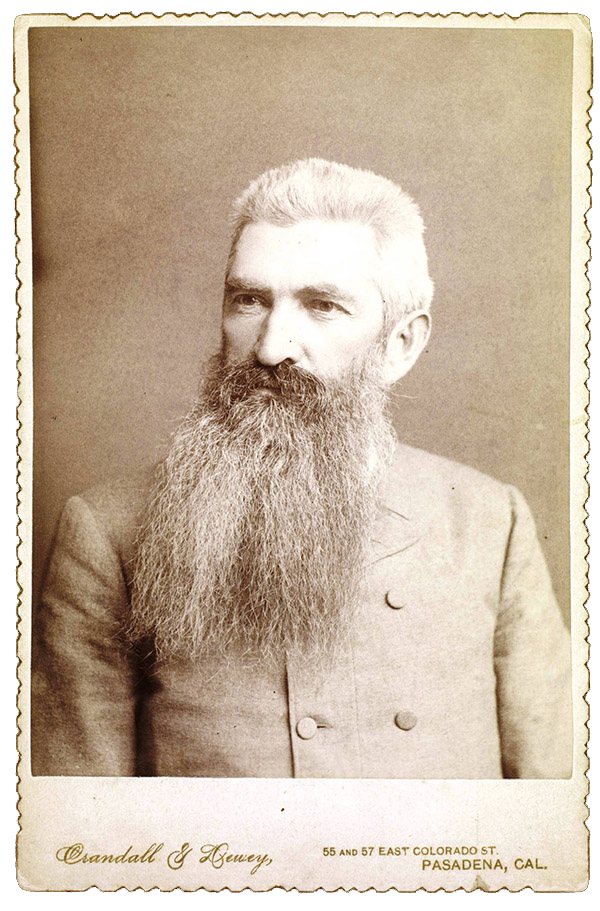

Owen and Jason Move to Pasadena

Owen, along with his older brother Jason, younger sister Ruth and her husband Henry Thompson, relocated to Pasadena during the 1880s at the urging of Major Horatio Nelson Rust, by then a successful businessman and horticulturist whose family knew and admired the Brown family as fellow abolitionists in Massachusetts.

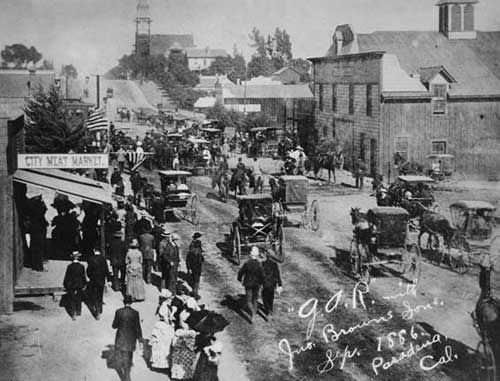

Pasadena had been founded a decade earlier by Union supporters from the Midwest, and so John Brown’s children were welcomed as heroes.

In 1886 the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a national pro-Union organization, held a parade on Colorado Street featuring Owen, Jason and Ruth.

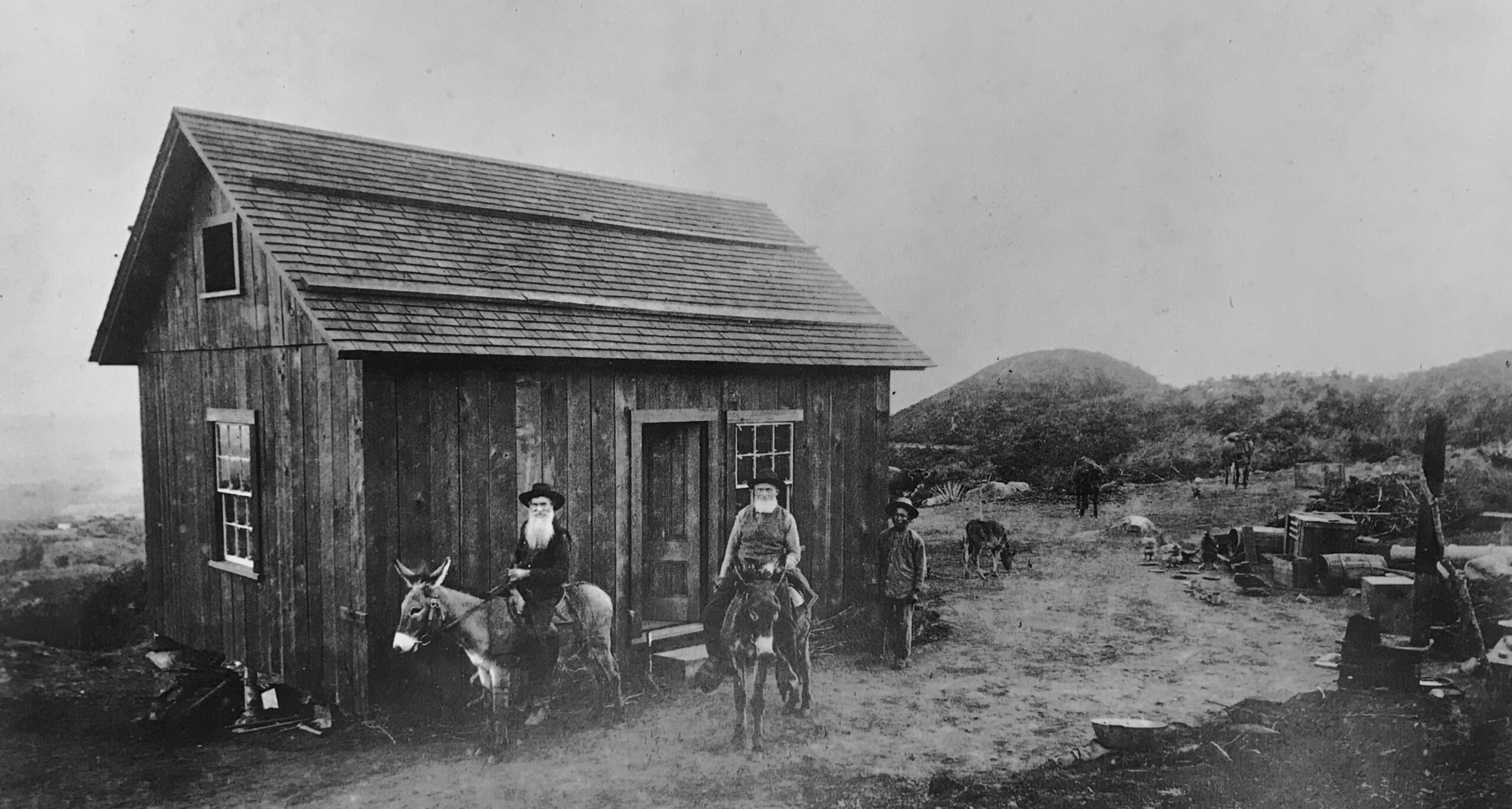

Ruth and Henry established their home in Pasadena. Owen and Jason homesteaded a parcel in the foothills above, in what is now the unincorporated community of Altadena’s “Meadows” neighborhood. They cut trails and roads, establishing rights of way that are still in use today, and built a cabin that became a magnet for visitors anxious to pay homage to these two sons of “The Liberator,” John Brown, and particularly to Owen as the last survivor of the raid on Harpers Ferry.

On one occasion their older brother, John Brown, Jr., and more than a dozen others, joined them at their cabin for this remarkable group photograph.

Owen never gave up his struggle for human equality. He supported the labor struggles back east, including the demand for the eight-hour day. In response to the despicable Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Owen and Jason hired Chinese workers in defiance of the bigotry then sweeping Los Angeles. There is a photo of the Brown Boys, as everybody called them, sitting proudly on their mules outside their mountain cabin, with a Chinese hired hand standing nearby.

Owen, although not conventionally religious like his father, embraced the temperance movement. On January 8, 1889, while staying at Ruth’s after a temperance meeting, he succumbed to a sudden case of pneumonia. The Pasadena Standard reported that 2,000 people—approximately half the population of Pasadena—attended his January 10 funeral at the Methodist Episcopal Tabernacle on Marengo Avenue, adding, “it is quite remarkable that there should be found in Pasadena so many men who were associated with John Brown in his mighty work, which up-heaved the nation and proved the entering wedge for the overthrow of slavery, thirty years ago.”

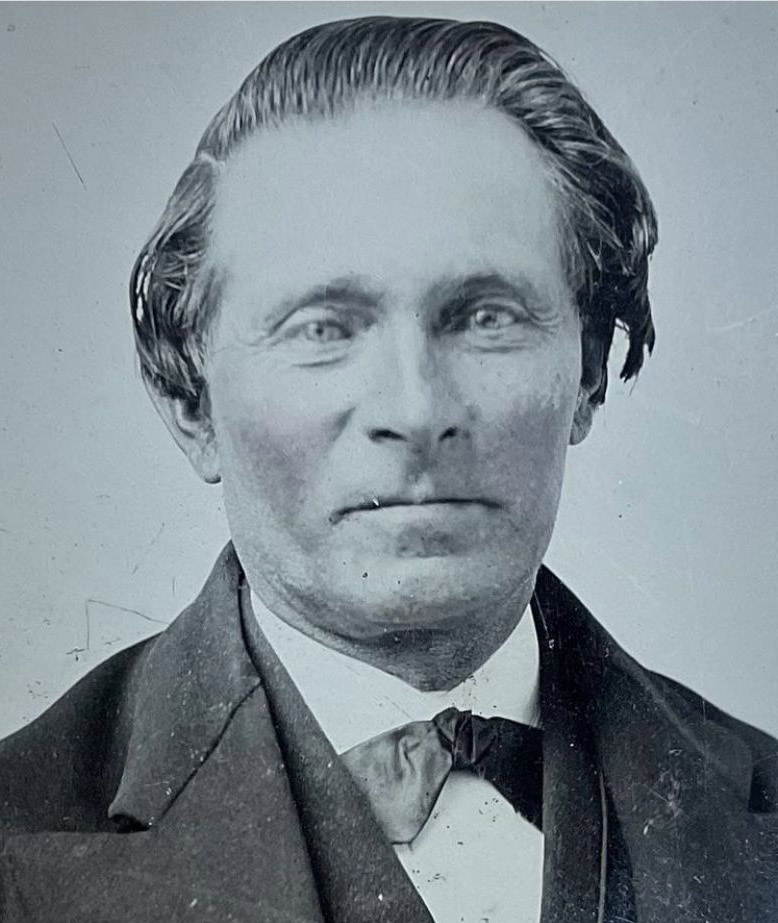

Dedication of the Owen Brown Granite Headstone, Saturday, January 29, 1898, with photo of Owen Brown (Insert)

Owen’s casket was transported eight miles to the knoll near the Brown Boys cabin they had named “Little Round Top” after the pivotal action on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Owen was interred on the summit with a simple wood marker and a cedar tree.

Nine years later, Major Rust commissioned a granite headstone meant to last for centuries as a monument to abolitionism. On January 29, 1898, 200 gathered on Little Round Top to commemorate the life of Owen Brown and his father.

Among the sermons, prayers and hymns offered that day, Rust concluded: “I am very thankful that so many have come up under the shadow of the Mother Mountains to mark in this most simple manner the grave of my old friend, Owen Brown. His service to his fellow man is a more lasting memorial. He gave the best years of his life with his father, John Brown ‘The Liberator,’ to uphold the cause of human freedom.”